Should B.C. adopt a category rating system for atmospheric rivers?

The term “atmospheric river” is new to many British Columbians, but the phenomenon that brought destructive floodwater and landslides is an age-old weather pattern. Now, one expert is urging the government to consider a category system for them, like the ones used for hurricanes and tornadoes.

The long, high plumes of moisture-laden air like the Pineapple Express can bring hours- or days-long rainfall of varying intensity to the west coast of North America, but as they become more common, it may be both helpful and necessary for the public and governments alike to know what’s on the way.

A University of Victoria climatology professor points out American researchers have already developed a five-stage scale, like those used for hurricanes, that could incorporate information Environment Canada already collects.

“That information can be directly piped from weather forecasts and other data into an analysis which calculates that category for the amount of water vapour that atmospheric river is packing at that moment," explained Charles Curry, acting lead at the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium.

"I think that would be a nice goal to have in mind for the future as a collaboration between meteorologists - who have this data at their fingertips and are able to forecast at least a couple of days ahead of time - and people on the ground who have to deal with the consequences."

Curry cautions that in the same way tornado and hurricane warnings can change in location and risk level, so too would an atmospheric river warning system.

"I think there are ways of expressing that uncertainty to the public as well, so they, along with emergency management, can manage the risk," he said.

Such a scale could also provide a framework for civic or provincial officials to enact the available Alert Ready system for flooding brought on by intense atmospheric rivers. B.C. remains the only province in Canada that hasn’t used the technology since 2019.

DEVELOPED IN CALIFORNIA, WITH WIDER APPLICATIONS

The one-to-five scale was developed by University of California researchers, who describe the weakest type of atmospheric river as “primarily beneficial” to their drought-stricken state, up to “primarily hazardous” for the top level.

"Currently, there is no concise method for conveying the spectrum of benefits and hazards faced by communities during a particular (atmospheric river) event,” the researchers wrote in an academic journal, explaining that weather forecasters, hydrometeorological scientists, and users of weather information penned the piece.

“If the AR event duration is less than 24 (hours), it is downgraded by one category. If it is longer than 48 (hours), it is upgraded one category.”

Even though the scale was developed and publicized in 2019, it has yet to be adopted by any government.

B.C. typically gets several atmospheric rivers each year, but with the warming climate, more are expected to sweep into the province, increasing the chance they’ll take unpredictable and destructive paths as they did last weekend.

B.C. DOES NOT HAVE A PROACTIVE WEATHER RESPONSE SYSTEM

Environment Canada publicly issues rainfall warnings, often revising the estimated precipitation up or down as weather systems develop. The B.C. River Forecast Centre provides advisories and warnings about stream and river levels, while DriveBC is tasked with aggregating road closures, weather conditions and traffic-oriented warnings.

Several B.C. ministers have defended their government’s messaging about the deadly weather event by pointing out that government social media channels and various websites had advisories in effect and available to any members of the public who knew where to go and how to find them through the weekend.

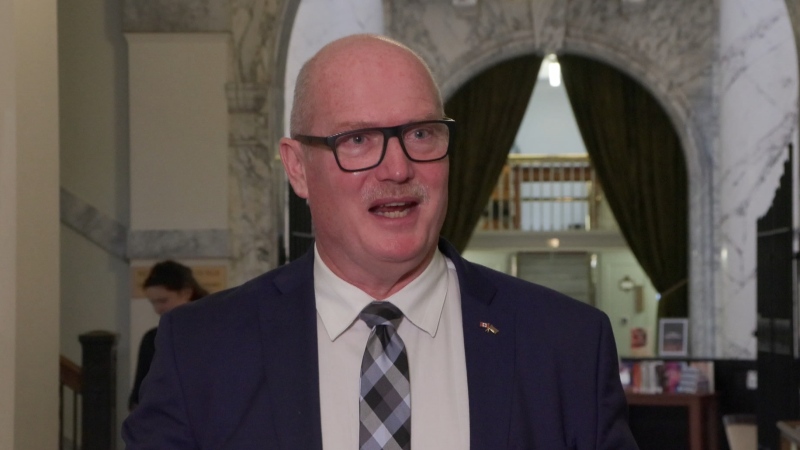

CTV News asked Transportation Minister Rob Fleming if B.C. has a system in place in which federal meteorologists work closely with his staff to proactively install warning signs or shut down sections of roadway already deemed to be at high risk for mudslides or flooding.

“We had contractors and ministry staff on a number of different highway systems looking at the impact of rain as it fell in the first 12, 24, and 36 hours,” said Rob Fleming. “The reality is, there are hundreds and thousands of kilometers affected by this once-in-a-century event.”

He did not say whether any roads were closed proactively, or whether staff waited until after slides and flooding had begun to do so.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

'They needed people inside Air Canada:' Police announce arrests in Pearson gold heist

Police say one former and one current employee of Air Canada are among the nine suspects that are facing charges in connection with the gold heist at Pearson International Airport last year.

House admonishes ArriveCan contractor in rare parliamentary show of power

MPs enacted an extraordinary, rarely used parliamentary power on Wednesday, summonsing an ArriveCan contractor to appear before the House of Commons where he was admonished publicly and forced to provide answers to the questions MPs said he'd previously evaded.

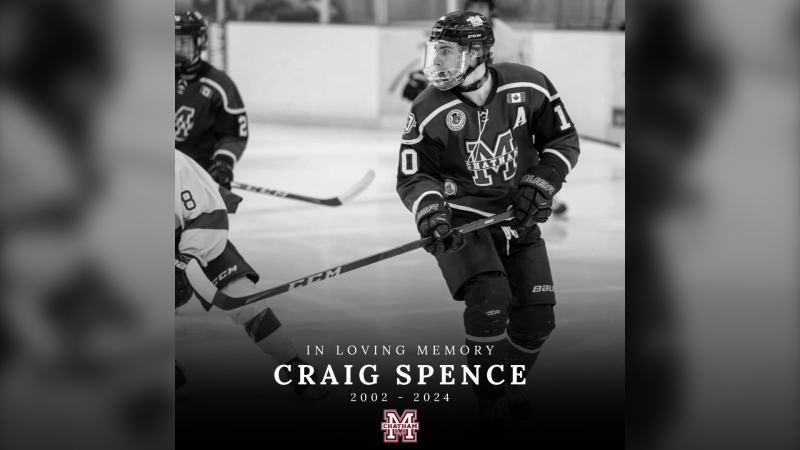

Leafs star Auston Matthews finishes season with 69 goals

Auston Matthews won't be joining the NHL's 70-goal club this season.

Trump lawyers say Stormy Daniels refused subpoena outside a Brooklyn bar, papers left 'at her feet'

Donald Trump's legal team says it tried serving Stormy Daniels a subpoena as she arrived for an event at a bar in Brooklyn last month, but the porn actor, who is expected to be a witness at the former president's criminal trial, refused to take it and walked away.

Why drivers in Eastern Canada could see big gas price spikes, and other Canadians won't

Drivers in Eastern Canada face a big increase in gas prices because of various factors, especially the higher cost of the summer blend, industry analysts say.

Doug Ford calls on Ontario Speaker to reverse Queen's Park keffiyeh ban

Ontario Premier Doug Ford is calling on Speaker Ted Arnott to reverse a ban on keffiyehs at Queen's Park, describing the move as “needlessly” divisive.

'A living nightmare': Winnipeg woman sentenced following campaign of harassment against man after online date

A Winnipeg woman was sentenced to house arrest after a single date with a man she met online culminated in her harassing him for years, and spurred false allegations which resulted in the innocent man being arrested three times.

Woman who pressured boyfriend to kill his ex in 2000s granted absences from prison

A woman who pressured her boyfriend into killing his teenage ex more than a decade ago will be allowed to leave prison for weeks at a time.

Customers disappointed after email listing $60K Tim Hortons prize sent in error

Several Tim Horton’s customers are feeling great disappointment after being told by the company that an email stating they won a boat worth nearly $60,000 was sent in error.