VANCOUVER – New drone footage from the University of British Columbia is providing a rare glimpse into the underwater behaviours of resident killer whales off B.C.'s coast.

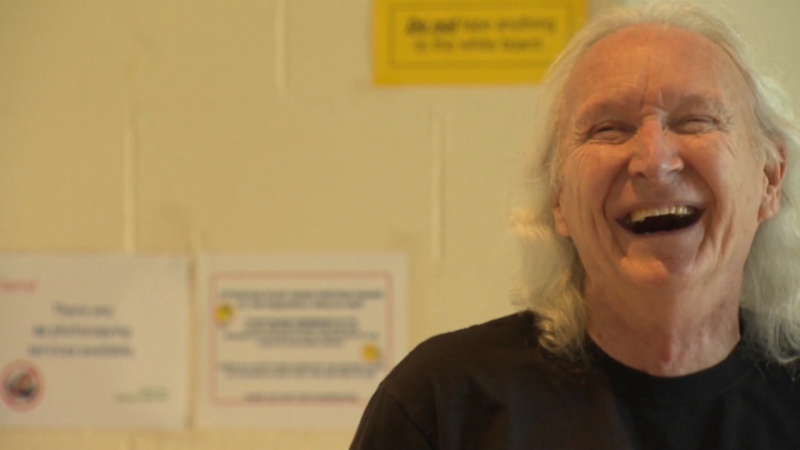

“For the first time we are using technologies to peer through all these layers of the ecosystem,” said Andrew Trites, project lead and director of the Marine Mammal Research Unit at UBC's Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries.

This is the first time drones have been used to study killer whale behaviour and their prey.

The footage, released Monday, was gathered in partnership with the Hakai Intitute and shows whales and their calves swimming and hunting together.

“What struck me most was to discover how tactile the whales are they are constantly rubbing into each other and touching one another. They are a lot like people right we hug our kids we hug our husbands and our wives it creates social bonds,” said Trites.

It’s all part of a five-year research project that is setting out to answer the crucial question of whether there are enough fish here for southern resident killer whales.

"In order to help these whales, we need to know more about them—how they hunt, how they forage and where their food is," said Trites. "It’s allowing us to be a fly on the wall and observe these animals undisturbed in their natural settings."

Just this past year, their population decreased from 76 to 73 whales. It’s prompted government action with the appointment of critical habitat zones where the whales forage for food as well as fishing closures along B.C.’s coast.

It’s too early to know if it’s working, but Trites says it’s looking promising.

“We didn’t see with the first impression any sign of a peanut head animal or have we heard any other reports from this summer seeing animals in poor condition,” said Trites.

Drone footage was captured over three weeks in late August and early September. Over that time, researchers observed pods of northern and southern resident killer whales and their prey.

"We were very lucky with conditions the whole trip and came back with ten hours of footage," said Keith Holmes, drone pilot for the Hakai Institute. "Normally, we were flying between 100 and 200 feet above the whales, often higher. They didn't seem to notice the drone at all."

Some of the first images captured showed southern resident killer whales feeding on salmon in the Salish Sea between UBC and the Fraser River.

Other footage showed the northern resident killer whales in Johnstone Strait off Vancouver Island and off Calvert Island in the central B.C. coast.

"We observed a northern resident mother with her new calf," said Trites. "From the boat, we could tell they were swimming near each other. But it was only from the drone that we could see how much they were constantly touching and socializing with each other."

Unlike the southern resident whales, the population of northern killer whales has increased significantly since the 1970s.

"It was amazing to see the southern residents zig-zagging along the surface as they chased and caught Chinook salmon," said Sarah Fortune, a postdoctoral fellow at MMRU. "Observing both populations of killer whales means we'll be able to compare the foraging conditions and hunting behaviours of the two groups and see whether it is more difficult for southern residents to capture prey."

In the months ahead, the data will be used to better understand the resident killer whales' feeding behaviour.

"I keep thinking back to the beauty of the mother and calf interacting with each other," Trites said. "It really drives home what's at stake for these whales if we don't figure out what's going on."

The research project is funded partly by the federal government, and data collected has the potential to shape future policy.

"Our research is helping determine is that food problem here in British Columbia?" said Trities. "Is that a Canadian-made problem or is it further south at the southern range of their habitat in California and Oregon?"