Supervised injection sites are delaying fatal overdoses, rather than stopping them altogether, a recovering addict says.

Earlier this week, CTV News visited a pop-up safe injection site located in an alley in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside currently being operated by volunteers. The site is technically illegal, but a legal location around the corner is so swamped that volunteers felt more needed to be done.

Within 15 minutes of arriving on Monday, CTV's Mi-Jung Lee witnessed two people overdosing at the site.

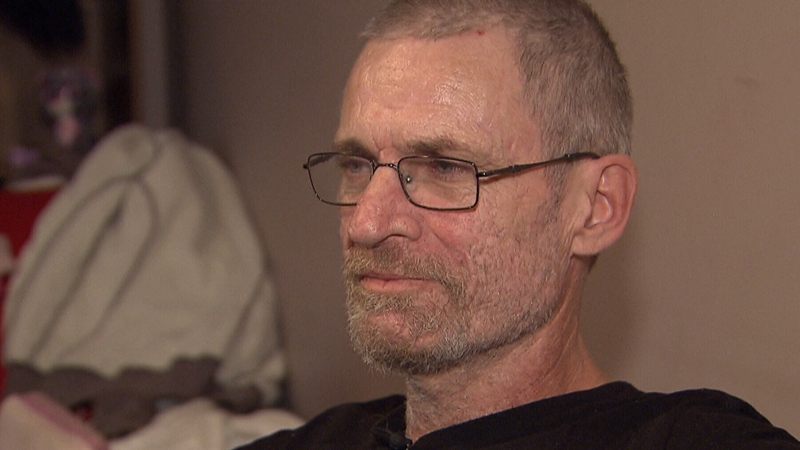

But Don Hills, a self-described "addict in recovery," said sites like those in the DTES are not enough in the battle against drugs.

"It's just enabling people that are using," Hills said Tuesday.

"Sure, there's not going to be maybe as many deaths, but that person that goes and uses it, there's going to be a time when he can't be bothered to go, and he's going to use somewhere else."

Hills said more needs to be done to stop addicts from buying and using in the first place, especially in light of an ongoing fentanyl crisis.

In the first 10 months of the year, 622 people in B.C. died of drug overdoses, compared to 397 during the same period last year. Fentanyl was detected in many of the deaths.

Hills, who said he's tried the manmade drug believed to be 100 times more potent than heroin, is fortunate not to be on the list of fatalities. The 55-year-old said he became an addict before he became an adult.

"I was in active addiction for probably about 40 years and I pretty well used everything," he said.

He started drinking alcohol when he was young, then moved on to "whatever was around, whatever was available."

He's used drugs including pot, mescaline, MDMA, pharmaceuticals, cocaine, crack, heroin and opium.

"Anything I could get I would use, it didn't matter, because I just didn't want to feel. I wanted to escape, really is what it was," he recalled.

Hills has been clean for four years, but said quitting was a major challenge, one that he tried every three or four months over his four decades years of drug use.

"But I always used again. And it was always on my mind… When I wasn't using, I was always thinking about, I can't wait until I get some, I've got to find a way to get some," he said.

Hills didn't discredit the work being done by volunteers on the Downtown Eastside, but said calls for more injection sites aren't the answer to addicts' problems.

In his case, he needed the support of a group, and he needed help tackling more than just the physical aspect of addiction. He needed people he could trust.

Hills said everyone is different, but that he believes counselling is the most effective treatment once people decide they're ready to stop.

Hills said there needs to be more support for addicts who've decided they want to change, especially at the beginning.

In the early stages of treatment, it doesn't take much for addicts to give up because they're used to turning to substances to solve everything, he said.

"They need counselling, they need peers – people they can talk to," he said.

And Hills' opinion is shared by some local experts.

Addictions specialist Dr. Jenny Melamed said when she sees the injection sites like those visited by CTV this week, she feels like something is missing.

"We're missing the concept of offering people recovery, and offering them the opportunity for a better quality of life," she said.

"We're just offering survival, and to me that is not recovery."

Melamed said that injection sites help keep people alive "from this injection to the next injection," but don't offer a long term solution.

But those who are looking to recover may have to wait, she said, noting that some treatment centres have an eight-month-long waitlist because their services are in such demand.

People who are looking just to detox may not have to wait, but anyone looking to check into a treatment facility may be waiting for months, Melamed said.

The province will cover costs for people on welfare, she said, but those who are able to work have to pay their own way. She said the treatment can cost up to $100 per day, and many programs are 28 days.

And she said most addicts need at least three months, and ongoing support after that period so they don't fall back into using once they've left treatment centres. The process is time-consuming, and expensive for those who aren't covered.

And Melamed and Hills both said that support outside of treatment is key to overcoming addiction.

"Addiction is such a complicated issue. It's physical, mental and spiritual. You can go into treatment and you get rid of the physical addiction, but then you obsess over it," Hills said.

"Something happens, you don't feel right, you want to use, you want to use, you want to use."

Spiritually, he said, people have their own values and rules, but "the more progressed your addiction gets, the more lines you cross, and you start doing those things you said you'd never do."

He said he's heard that many think drug users are angry, but that addictions are often based on fear.

"We're afraid of everything. We're afraid of ourselves, our emotions… anger is such a strong emotion it covers all the other emotions, so you don't have to feel, and that's why they're always angry. But deep down inside, they're afraid."

Hills said he spoke to the media because he wanted to deliver a message to those currently struggling with addiction: "Believe in yourself. Love yourself enough to live life, instead of exist."

With a report from CTV Vancouver's Mi-Jung Lee