A program that’s supposed to help gambling addicts at B.C. casinos–but often lets them in to lose huge amounts of money–will be reviewed as part of the province’s overhaul of the industry in response to money laundering concerns.

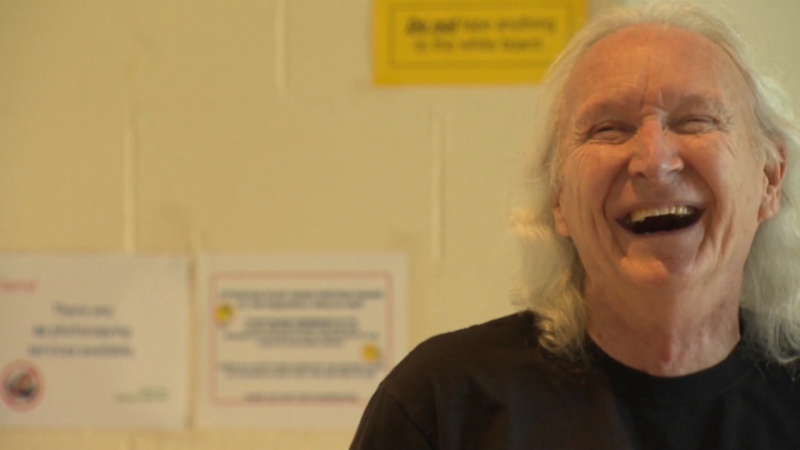

The news comes after the latest expose of the Voluntary Self-Exclusion Program, this time by Nik Galego, a Vancouver Island man who had signed up for the program after his life was turned upside down by his losses.

“What I’m about to do tonight, it makes my heart pound. It’s beating out of my chest right now,” Galego says on a video he recorded on his cellphone outside the Courtney Chances Casino.

“Gambling has destroyed my life. Gambling has destroyed my personal life, my financial life, my health….This is just an experiment to see if anyone cares.

“Tonight I’m going to put you in my pocket and see what happens,” Galego says, pointing his cellphone forward and walking towards the casino door.

The Voluntary Self-Exclusion Program is designed to deter problem gamblers and gambling addicts by stopping them at the door, marching them out of the casino if discovered, and seizing their jackpots.

Galego’s video shows that no one stopped him as he entered the casino. He gambled $20 at several slot machines and was not discovered.

“So three security guards at the front door did not ID me at all,” he said. “None of them paid much notice. It’s pretty sad."

It’s a similar conclusion that a CTV News hidden camera investigation came to eight years ago, when a producer who signed up for the program was promised he would be kept out, but was let in to gamble.

Disaffected members of the program have complained of enormous losses, suicidal thoughts and destroyed families.

There are about 10,000 people on the program, and it’s difficult for security guards to keep track of that many faces. About 10,000 people a year are turned away, but BCLC doesn’t know how many people get in to gamble.

The story was not a surprise to B.C.’s attorney general, who said he knew of other such cases covered by the media over at least a decade. The earliest such story on CTV News was in 2001.

“It’s not a perfect program,” said David Eby. “We’re looking at ways to improve the program. We can do better.”

One opportunity: the large-scale review of the Gaming Control Act prompted by widespread money laundering discovered in some B.C. casinos in a government report that suggested some casinos had taken in more than $100 million in dirty cash.

“We’re doing a full review of the Gaming Control Act and hopefully as part of that we’ll find opportunities to improve the program,” Eby said.

BCLC doesn’t keep track of how much money is lost by gamblers on the program. But it does keep track of seized winnings – about $400,000 a year – some of which are then sent to gambling researchers.

That is likely a fraction of the money gamblers in the program lose, said Robert Williams of the Alberta Gambling Research Institute.

“To win a lot of money, you’ve got to lose a lot of money. That’s how gambling works. It would be many multiples of that four hundred thousand, but it’s difficult to quantify,” he said.

Williams said the program is effective for some people. He said he had done dozens of interviews explaining the flaws in various versions of the Voluntary Self-Exclusion Program across the country through the years, and was encouraged at the possibility that B.C. might be responding to the years of coverage.

“The cynic in me argues there’s too much money involved,” he said.

“Even though they constitute only two per cent of the general population, the gambling addicts’ average expenditure is extremely high. Maybe a third or half of casino revenue comes from that two per cent,” he said.

A lawsuit from several gambling addicts lost at B.C. Supreme Court – one sign that the casinos don’t owe a legal duty of care to the addicts. But settlements in Ontario in similar cases suggest the law isn’t yet settled, he said.

Casinos in countries outside North America solve this problem simply by asking for ID at the door, and checking it against a list, he said.

“People have ID for all sorts of things. There’s no good justification for not doing that for casinos, especially in light of the harm that it’s causing,” he said.

Eby said the province needs a legislative mechanism to collect that kind of data about its citizens, but said the government would explore the possibility of ID checks.

“Anyone with a gambling addiction shouldn’t be gambling in the program and we’ll look at ways to improve it,” he said.

Galego said he supports the idea of an ID check.

“Is this how every casino works? Are you able to freely walk in there with no problem? If that’s the case, something needs to change here,” he said.

BCLC didn’t agree to an interview, but said in a statement it’s committed to helping problem gamblers.

“Helping to support healthy gambling amongst our players is a key priority for BCLC, and the VSE program is one component of a multi-faceted player health program to encourage positive play behaviour amongst our players through education and support,” the statement said.