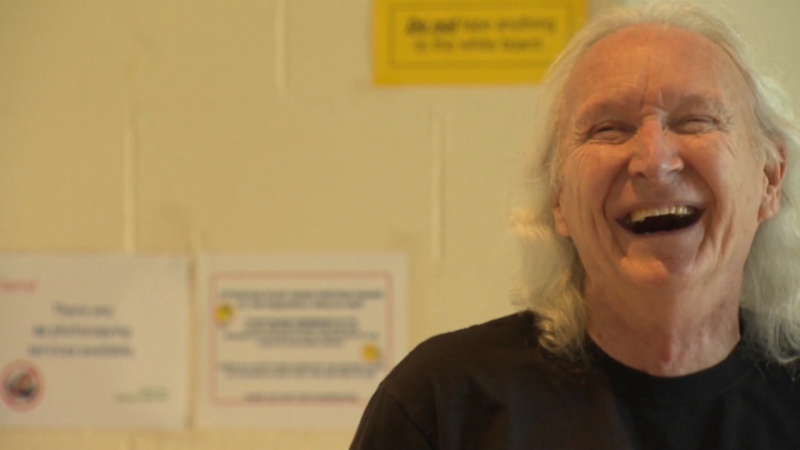

A University of British Columbia professor who specializes in public health said he hopes to soon dispense opioids through a vending machine on Vancouver's Downtown Eastside in order to prevent overdoses from fentanyl-laced street drugs.

Dr. Mark Tyndall said the eight-milligram hydromorphone pills – which are a substitute for heroin – cost about 35 cents each. Focus groups with drug users have suggested most people would need about 10 to 16 pills a day, he said.

Tyndall's prototype is ready and he hopes the vending machine can be tried out on a small, regulated scale in the next few months.

CTV News Vancouver spoke with Tyndall about the vending machine. Below is part of an eight-minute interview, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Question from CTV News Vancouver's Emad Agahi: Tell us what your proposal is for the machines?

The idea of using dispensing machine for drugs is something that I've been working on for almost two years now. We're finally at a point where the prototype is ready to go and I'm trying to present this as a scalable model to allow people access to safer, regulated supply of drugs.

I don't really mind how we get them out there, but I think as the overdose crisis has continued, we're at the point where everybody's talking about a safe supply. We cannot go on letting people knowingly buy these things in alleys, and products of unknown quantity and unknown quality and not offer them some kind of alternative.

How would they work?

We'd use hydromorphone pills to begin with – the machines could be stocked with a lot of things – but the first step would be to follow what we've learned from the Crosstown Clinic, where people have been using hydromorphone and with some success, so we can use what we've learned from that to dispense these in a regulated form.

People should realize this is a proposal that would be quite strict so only certain people would get access to the program. It's a biometric machine, so only the people involved could access it. It's all programmable as far as the quantity and dosing and timing of this so it's quite a regulated way, although it allows people some autonomy when and where they can pick them up.

How will people be selected to use the machine and how will it be regulated to make sure it can't be accessed by anyone?

Well that's the brilliance of the biometrics. There's no PIN or cards. People would obviously have an enrollment procedure so we know who's getting them and we know about that person, but once they're enrolled, you stick your hand up to the machine, it recognizes you right away … it's an ironclad way to ensure that the person we want to get the medications is getting the medications.

It's an 800-pound steel machine. It's more like an ATM than what people think of a vending machine so people would not be able to break into it or carry things away.

Who will be supplying the drugs?

When we start the program, I think we would have to stick to the current regulations as far as prescribing. So a doctor would have to prescribe these medications to somebody.

I think as a public health approach, we should be aiming for people who fill a certain criteria and then it would not be up to a doctor to prescribe them, that the province would supply the drugs. But as it stands now, to get it going, an individual doctor would prescribe to an individual patient and then they'd monitor their uptake of the drugs.

Any concern of these drugs being distributed to people who don't have a prescription?

We have a lot of experience of people getting drugs from a pharmacy and some of them go missing or go to other places. So if somebody asked me, "Can you guarantee that none of these pills would ever get to somebody that wasn't on the program," I'd say probably not. It will happen.

But under the current situation, most people that we've talked to through focus groups would be using them themselves. If the alternative is buying poisoned drugs in an alley, or getting a supply yourself, the vast majority of these pills would be used for the intended purposes and if any went astray, I'm pretty sure they would go to close friends and partners and other people in trouble at the time.

It's possible some of them may go to other people but I would think a very small proportion and, under a poisoning epidemic, that's not the worst thing in the world to save somebody buying them from the street anyways.

Anything else?

I think there's a lot of talk about a safe supply but we really need to get down to a practical application of this and we should be asking a lot of new ideas. So I'm not saying this is the only thing that could ever work, but for a certain proportion of people I think this could be highly effective and we just have to take some chances and move on these things.

With files from The Canadian Press