Health-care professionals who look after one of the province’s most vulnerable populations—incarcerated patients—came together in Vancouver Friday to envision better ways to provide mental health care in prisons.

The conference was the first of its kind that was organized by a Vancouver-based prison legal clinic. Jennifer Metcalfe, one of the organizers and executive director of the West Coast Prison Justice Society, said the timing is especially important because B.C. is in the process of transferring responsibility for prisoner health care from Chiron, a for-profit company contracted by the Ministry of Public Safety, to the B.C. Ministry of Health.

“I think people are really optimistic about quality of health care improving,” she said.

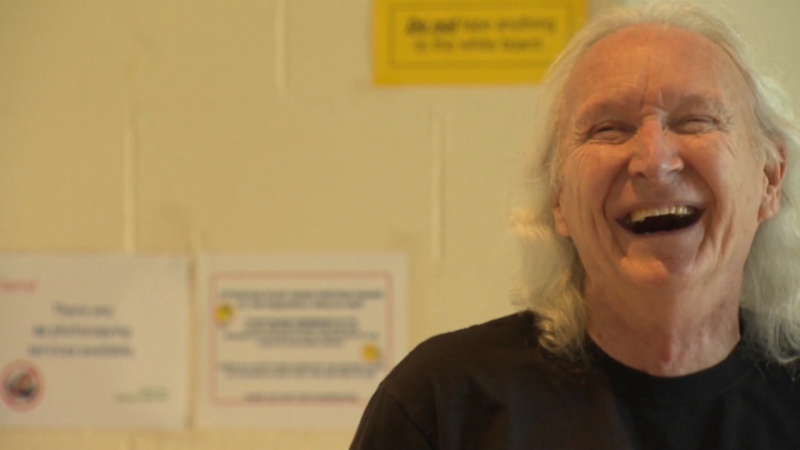

Speakers at the conference included Dr. Gabor Mate, an expert on addiction, Howard Sapers, the Ontario correctional investigator and Dr. Ruth Elwood Martin, a prison physician who’s supported a mother-baby program at Alouette Correctional Centre for Women.

For Metcalfe, improving mental health care for prisoners is important not only because so many incarcerated people have a history of trauma and addiction, but also because it will improve public safety.

“If we take a more therapeutic approach to people’s behavioural problems then we’ll do better at rehabilitating people and reintegrating them to society as law abiding citizens,” she said.

One of the biggest problems with the way prisoner mental health is currently dealt with, in Metcalfe’s view, is the use of solitary confinement. Her organization, West Coast Prison Justice Society, advocates for solitary confinement to be abolished.

“They depend on people being able to maintain good behaviour being isolated for most of the day,” Metcalfe said. “It’s really hard for people, especially if mental disabilities, to hold it together under those conditions.”

Right now in B.C. prisons, being held in solitary confinement, sometimes called the Enhanced Supervision Program, means an incarcerated individual is kept in a small cell for up to 22 hours per day.

“I think it’s more effective to give people meaningful human contact, access to therapy,” Metcalfe said. “Instead of depriving them of meaningful human contact which we know results in anxiety and paranoia.”

She said she was pleased by the recognition from attendees that putting people in solitary is not a good solution.

“We don’t want to be walking the line of torture or cruel treatment,” she said. “We have an opportunity when [people are] in custody to help them heal and become productive members of society. And we should take that opportunity.”