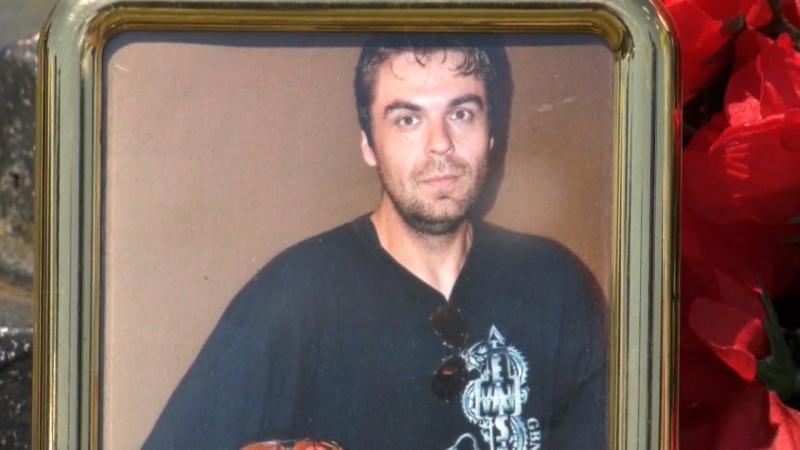

It’s been seven months since Chris Saini and Shelley Sheppard lost their only son.

“A lot of people think that with grief you kind of move on and things will get better, but that’s not the case,” Sheppard said.

In February, a CTV News Investigation revealed that the operator of the unlicensed East Vancouver daycare where 16-month-old Macallan Wayne Saini, known as Baby Mac, died had been visited by health officers following a complaint.

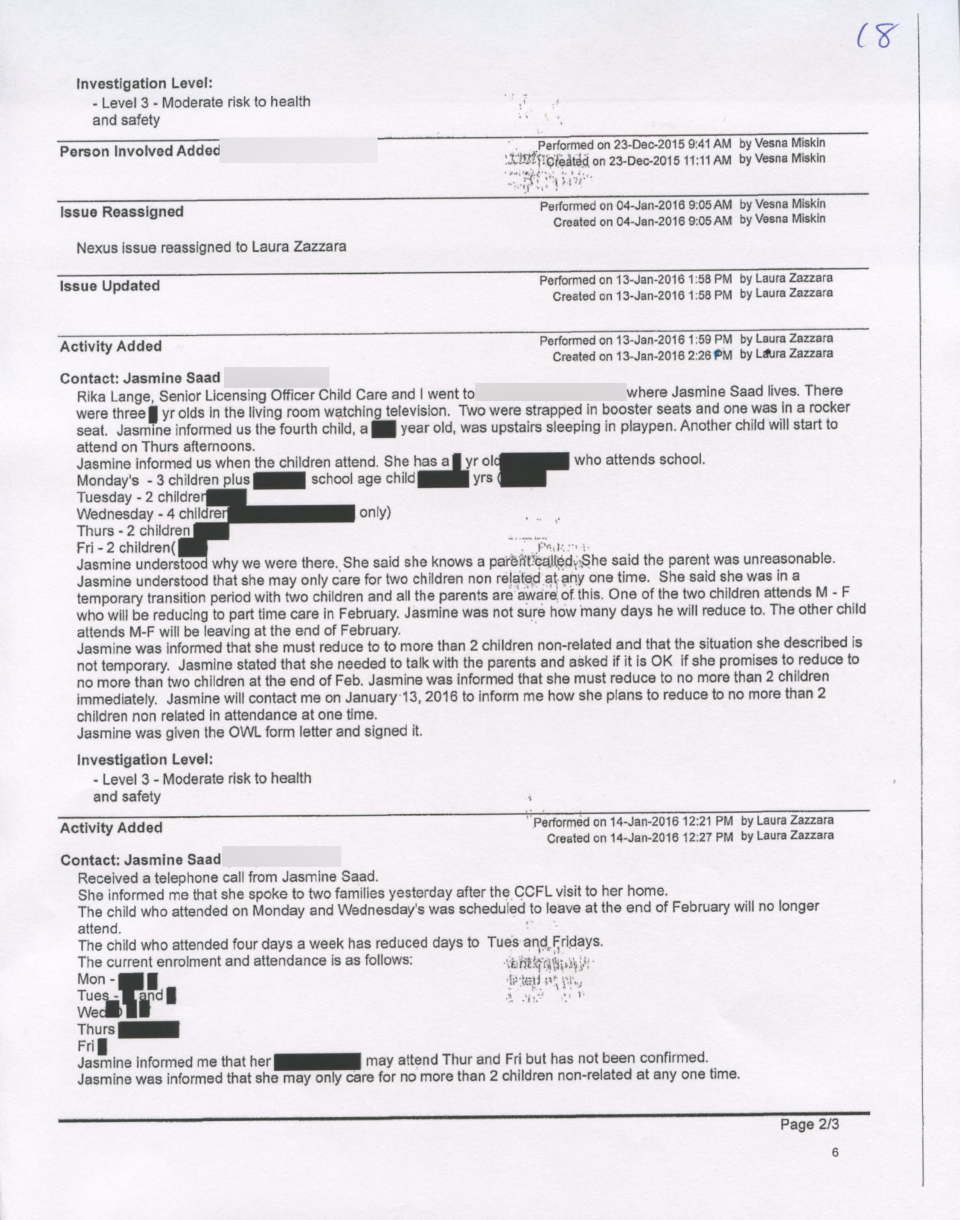

Now, documents obtained by CTV News show that operator, Yasmine Saad, had been previously investigated four times, at four different addresses, in the seven years before Baby Mac’s death.

During three of those visits, the documents show, licensing officers with Vancouver Coastal Health found that Saad broke the law by having too many children in her care.

The records, obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, show an apparent pattern, indicating Saad was aware she was violating childcare regulations, and that while licensing officers expressed concerns that she was a repeat offender, they did not appear to escalate the matter, nor use any of the enforcement tools available to them.

The documents took CTV News almost four months to obtain. Unlicensed daycare complaint and inspection records in British Columbia are not easily accessible, nor made public.

“Almost physical sickness was our first reaction,” Saini said, after reviewing the records for the first time. “Eventually, that just turned to anger.”

“[Vancouver Coastal Health] knew that there was issue with [Saad] being compliant to the law,” Sheppard said. “She continued to do what she wanted to do, and there were no consequences.”

The paper trail

Under B.C.’s Community Care & Assisted Living Act, unlicensed childcare operators are allowed to care for a maximum of two children, other than their own. There are exemptions for children related to the operator by blood or marriage, and for sibling groups.

In April 2010, Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) licensing officers visiting Saad’s “Olive Branch Family Daycare” at a home on West 16th Avenue found six children in Saad’s care, according to the documents. The visit came after a complaint from a parent.

“You appeared to know that without a [license] you may care for a maximum of two children,” they wrote in a letter to Saad, dated two days after the visit. “You agree to reduce the number of children…and to stop promoting yourself as a Licensed Family Child Care.”

Records show when licensing officers visited Saad two weeks later, no violations were found.

In May 2012, VCH licensing officers, following up on a complaint at a Beatty Street condo, found Saad caring for three children:

“It is of serious concern…that in the past you have been found to be in contravention of the [Act]…and it appears you knowingly continue to contravene the Act,” Officers wrote. When Officers followed up with Saad the next day, records show no one answered the door. Documents do not indicate any follow up visits or phone calls by VCH to Saad in 2012.

In January 2016, following up on another complaint, VCH licensing officers visited Saad at a house on McSpadden Avenue, and found four children in Saad’s care.

“Jasmine understood why we were there,” one officer wrote in her notes, under the heading “Level 3 – Moderate risk to health and safety.” “Jasmine understood that she may only care for two children non-related at any one time.”

Records show a VCH officer received a phone call from Saad the next day to inform the officer how she planned to reduce the number of children in care.

There are no further records of follow up visits or phone calls to Saad by VCH officers in 2016. A little over one year later, at a home on Kitchener Street, Baby Mac died while in Saad’s care.

Shelley Sheppard believes Vancouver Coastal Health should be held accountable for Mac’s death.

“They did not follow through on their jobs. They did not provide any consequences to her breaking the law,” she said.

In fact, the documents show VCH licensing officers told Saad she could be liable to penalties under Section 33 of the Community Care & Assisted Living Act, which allows for fines of up to $10,000 per day for violations.

“That’s a pretty hefty sum,” said Chris Saini. “I think if you got dinged with that once, even twice, you’re not going to break that rule again.”

There is no indication Saad was ever fined.

Sharon Gregson of the Coalition of Childcare Advocates of B.C., and a chief backer of the universal “$10 a day” childcare plan B.C.’s new NDP Government has promised to phase in over the next decade, says she’s not surprised:

“I have never seen the $10,000 penalty enforced,” Gregson said. “In fact, I don’t think many people are aware of it.”

Yasmine Saad and her lawyer did not return repeated emails and phone calls requesting comment. And while Vancouver police have told CTV News the cause of Mac’s death is “not suspicious,” the case remains under investigation. No charges have been laid.

The search for answers

When CTV News went to Vancouver Coastal Health to ask why Yasmine Saad wasn’t fined, or why licensing officers didn’t appear to escalate their concerns, spokesperson Anna Marie D’Angelo declined “to speak to specifics,” and directed us to the Ministry of Health, which in turn pointed us to the Ministry of Childcare and Family Development.

“What good is it having a law on the books with those consequences, if there are no consequences?” I asked Minister Katrine Conroy, who had been on the job only a few weeks.

“It’s unacceptable,” Conroy answered, adding we would have to “ask the previous administration why she wasn’t fined.”

“I agree with you, that doesn’t seem right.”

Conroy said the province is working hard to make sure there is good licensed care in place for children.

“We work to make sure that licensing is doing its job,” she said, adding: “If the regulations are there, they need to be followed.”

As part of the $10 a day universal childcare plan, the NDP has promised 22,000 new licensed spaces over the next three years, and 66,000 within five years.

Conroy also committed to making unlicensed daycare inspection records available online, where all parents would have access to them.

When asked whether more licensing officers and inspectors are needed, she said: “Potentially yes.”

Conroy also said “potentially yes” when asked if there’s a need to make an example of people who aren’t doing things right, or are violating the law.

“That’s part of the plan,” Conroy said, pointing to a letter sent by the Ministry of Health on Aug. 3, asking health officers to use the “enforcement tools that are available,” particularly with repeat offenders.

But the Minister stopped short of calling for an outside, independent investigation into Vancouver Coastal Health’s handling of the case, as the health authority conducts its own internal review.

“That’s something I’ll be talking to [Health Minister Adrian] Dix about,” Conroy said.

“Depending on where things are at, it’s something we’ll be discussing.”

Conroy also said she would have a conversation with B.C.’s Attorney General about whether Saad could still be fined.

And the minister confirmed for the first time that as the investigation into Baby Mac’s death continues, Saad has no children in her care.

A call for change

While Chris Saini and Shelley Sheppard have become outspoken advocates for universal childcare, Baby Mac’s parents say these promises are too little, too late.

“Why the hell didn’t they do anything before?” Saini said. “If they did this before, Mac would be alive.”

“I hope there’s some sort of policy change, their mandate changes, so this doesn’t slip through the cracks again,” Sheppard added.

Baby Mac’s parents are still struggling to come to terms with their son’s death. They say the coroner has still not released the autopsy results, and they still are waiting for the clothes their son was wearing that terrible day to be returned.

When asked, Minister Conroy refused to call the corner, but called the delay “totally unacceptable.”

The BC Coroners Service would not comment about Mac’s case. “While we acknowledge that families would like investigative results quickly,” wrote communications manager Andy Watson, “It is sometimes not possible to provide quick answers in these type of investigations.”

And while Baby Mac’s parents say they understand nothing will bring their son back, their worst fear is that what happened to Mac could still happen to someone else’s son or daughter.

“I’m just so mad,” Saini says, choking back tears. “I’m just so mad that the government, the system failed us. They failed my son. Forget about our grief. Forget about all of that. My son lost his life.”

“I hope in the future that we can have affordable, safe, quality childcare for our kids,” Sheppard added. “That’s Mac’s legacy. I hope that we can leave that for him.”