BURNABY, B.C. -- Erica Salemink still has the golden cross her mother, Colette, was wearing around her neck when she died. Slightly crooked and still smeared with soot from the fire that killed her, the cross now hangs in a memory box next to Colette's photo.

Colette, a 59-year-old woman from Coquitlam, B.C., had the cross made from scrap gold and picked it up just a week before her mentally ill son set her house ablaze in the early hours of April 19, 2010.

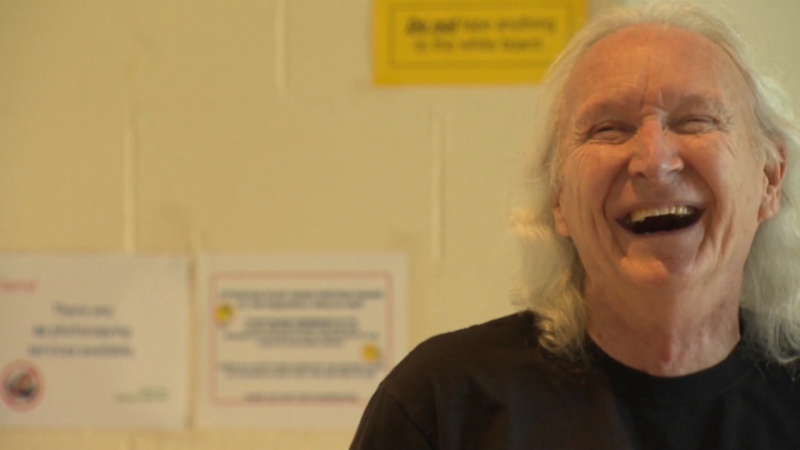

"She felt in all the jewelry stores, they were all too perfect," Erica recalled through tears Thursday at a coroner's inquest into her mother's death.

"She had a cross made that was slightly off-kilter and not perfect, and I think that says a lot. Her faith was strong, but she knew that it couldn't provide her with the perfect answers."

There were few things that were perfect in Colette's life with her troubled son, Blake, and even fewer answers about how to deal with him.

Blake, who suffers from a combination of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder known as schizoaffective disorder, was eventually charged with manslaughter and arson in his mother's death, but he was declared not criminally responsible earlier this year because of his mental illness.

At the time of the April 2010 fire, Blake, then 23, was on leave from a psychiatric hospital on strict conditions that he live with his mother, but their relationship had grown increasingly fraught and, at times, violent.

Five months earlier, Blake assaulted Colette, leaving her with bruising on her face, but he wasn't arrested or charged and his doctors weren't told what happened.

Colette called Blake's mental-health team for help, telling them a week before the fire that she couldn't handle her son any longer. She was told the only way to remove him from the house was to get a restraining order.

And two days before she died, Colette phoned the police after Blake threatened to kill her, either with the help of a hit man or by himself. Colette told police it was an idle threat and she didn't want her son charged, but neighbours said she appeared terrified.

Throughout it all, the police weren't aware of Blake's illness or that he was on leave from a psychiatric hospital. Blake's doctors, in turn, didn't know about the death threats or the full extent of the assault. Information wasn't shared, the inquest has heard, partly because privacy laws wouldn't allow it.

Erica said her mother was torn between protecting herself and looking out for her son, but no one stepped in to help her sort that tension out.

"Her unconditional love, I believe, made quite a tug-of-war with her heart when dealing with Blake and what was best for her," said Erica.

The family didn't want to see Blake homeless.

"She was trying to figure out a way to do the right thing with both her and Blake."

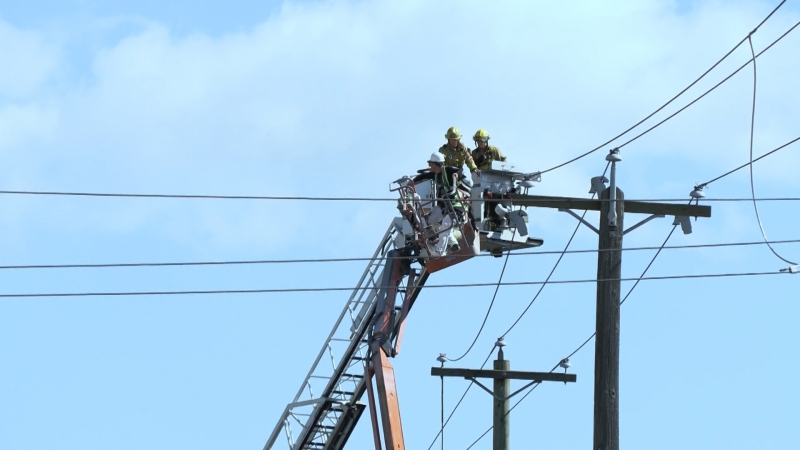

The inquest jury recommended Thursday that RCMP, Port Moody Police and the Fraser Health Authority develop a co-ordinated approach for dealing with mentally ill people that would include sharing information.

They said it should include meetings between police, mental health and corrections officials to deal with privacy and mental health.

It was among 16 recommendations from the jury.

Others dealt with issues such as police training on mental health issues and allowing police to temporarily revoke extended leaves for people who break their conditions and take them to a mental health facility.

Erica, whose four-week old son was in the inquest room, told the coroner's jury there should be more resources for people with mental illness and their families, particularly when they need help on the evenings and weekends.

She said if Blake's behaviour was deteriorating after hours, his mother's only option would be to call the police and ask that he be taken to a hospital. Colette phoned a nurse's hotline once to ask if there were any mental health workers who could come by and assess her son, Erica recalled, but she was told there was nothing like that available.

"Even if you have someone available on weekends and nights when everything else is closed, because that was also a problem for us that weekend (after the death threat), is that everything had to wait until Monday or the next appointment," said Erica.

"There's nothing available."

She said police officers should also be trained on what she describes as active listening to ensure they are able to assess the complicated dynamics of family conflicts that involve mental illness.

Blake is now at the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital in Port Coquitlam, also known as Colony Farm.

Testimony at the inquest wrapped up on Thursday, leaving the case in the hand's of the coroner's jury.

The jury can issue recommendations aimed at preventing similar deaths in the future but cannot assign blame.