More B.C. parents say kids won't get critical medication in schools after policy change

More B.C. parents are coming forward saying a bureaucratic change by the province means their children are no longer eligible to receive potentially life-saving medication at schools, despite being at risk for serious seizures.

If Carmen Elzinga's daughter Naya has a seizure at her Burnaby school she's been told staff soon won't be allowed to give her medication.

"If someone doesn't administer that within five minutes, then she is at high risk of brain damage," Carmen told CTV News.

Naya's neurological condition resulted in 29 surgeries by the time she was seven. Her mom says the seizures don't stop on their own and require medication.

The health ministry recently changed its policy on who qualifies for in-school intervention. If a child hasn't had a serious seizure within the previous 12 months -- starting in September -- staff won't intervene. Instead, a parent or 911 will be called.

Elzinga said she and her husband are now planning for one of them to always be within five minutes of the school.

"They're basically forcing us to choose between the well-being of our daughter and us earning a living," she added.

Hampton Gaudet is in a similar position. His parents say he's had 20 seizures this year at school , but also doesn't qualify under the new policy.

The Health Ministry didn't respond to CTV's questions and instead sent a statement from Saturday describing the new policy.

"To be eligible for Seizure Rescue Intervention Care Plan, a child must have required a rescue intervention over and above basic seizure first aid to stop their seizures. (Seizure first aid includes putting the child in the recue position, maintaining their airway and monitoring them.) If it has been more than 12 months since a child has needed a seizure rescue intervention (medication), the child will be transitioned off an NSS Seizure Rescue Intervention Care Plan and into a Seizure Action Plan in the school setting."

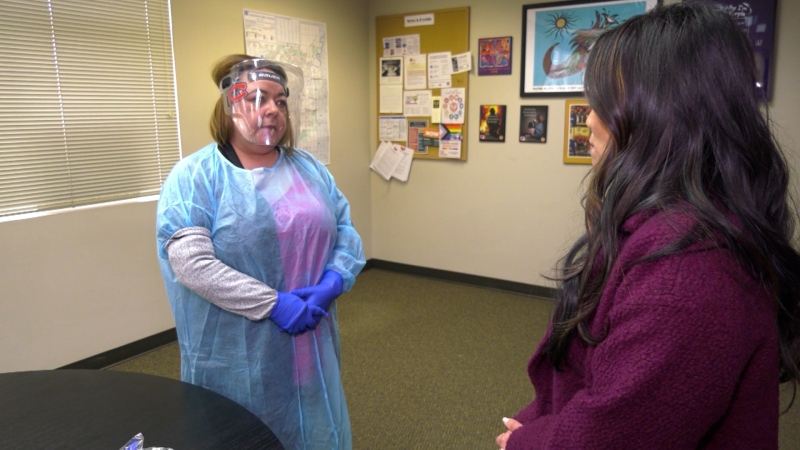

A video from the Cleveland Clinic shows how Naya's medication is administered. After extracting a precise amount, the needle is removed, an atomizer inserted and sprayed into a child's nose. This type of work is typically done by nurses -- but sometimes school staff -- like education assistants -- are trained in case of emergency.

A document explaining the change says a child who hasn't had a seizure in a year could have an acute and unpredictable response and requires a higher level of care then school staff can provide.

Elzinga is frustrated by the change.

"Even if she was to have a seizure, no one at the school would do it. Even if they're trained to give it to another child," she said.

By sharing her story she's hoping the province will reconsider the move for the sake of the families now concerned about their kids' safety.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Man sets self on fire outside New York court where Trump trial underway

A man set himself on fire on Friday outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump's historic hush-money trial was taking place as jury selection wrapped up, but officials said he did not appear to have been targeting Trump.

Sask. father found guilty of withholding daughter to prevent her from getting COVID-19 vaccine

Michael Gordon Jackson, a Saskatchewan man accused of abducting his daughter to prevent her from getting a COVID-19 vaccine, has been found guilty for contravention of a custody order.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

The Body Shop Canada explores sale as demand outpaces inventory: court filing

The Body Shop Canada is exploring a sale as it struggles to get its hands on enough inventory to keep up with "robust" sales after announcing it would file for creditor protection and close 33 stores.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

On federal budget, Macklem says 'fiscal track has not changed significantly'

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem says Canada's fiscal position has 'not changed significantly' following the release of the federal government's budget.