Some of Canada's most vulnerable women have for decades disappeared or been found dead, and now the country's justice ministers admit it's an epidemic that hasn't received the attention it deserves.

After a meeting this week in Vancouver, federal, provincial and territorial ministers released a report with more than four dozen recommendations on how to protect women living high-risk lifestyles.

The ministers said the problem is about more than B.C. serial killer Robert Pickton, or convicted Albertan killer Thomas Svekla. In fact, the issue is Canada-wide.

"The positive thing that has come out of this is that there is a recognition that this has not received the attention it deserved," federal Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said Friday.

There needs to be much greater co-operation between everyone involved and that's the commitment from the ministers, Nicholson pledged.

The report was compiled by a missing women's working group. The group was established to look into the problem more than four years ago.

"The missing women working group recognizes the serious harm done to women, families and communities by serial predators who target marginalized women," the report says.

It recommends an infrastructure change to prevent women from going missing, and to track their cases when they have vanished or been murdered.

The working group made 51 recommendations in order to protect women from serial predators who target victims because of their "availability, vulnerability and desirability."

Among the recommendations are that a national plan be set up for reporting missing people, that police use compatible case management software and that a national missing person database be established for both police and coroners to access.

The working group found that policies, procedures and structural responsibilities for missing people vary widely among police agencies.

In murder investigations, the report said failure to make connections between cases is referred to as "linkage blindness." It said the key contributor to that blindness is lack of information and lack of co-operation in sharing information.

That same issue was one of several highlighted by the Vancouver Police Department when it released a report on the investigation into women vanishing from the city's Downtown Eastside.

The B.C. government has called an inquiry that will examine the police investigation and how Pickton was allowed to remain free while more women kept disappearing.

He was convicted of killing six women, but the DNA of 33 women -- most of them drug addicts or sex trade workers -- was found on his pig farm.

Host of the minister's conference, B.C. Attorney General Mike de Jong, said people are still asking how that many women could go missing over such a relatively short period of time without it registering.

De Jong said the answers could have national implications.

"How do we organize ourselves to effectively ensure that we are sharing information, that the degree of integration exists that is necessary to identify that a serial killer is actually operating in an area?"

The report also recommends that victims and witnesses get support in higher-profile cases, such as the Pickton and Svekla murder trials.

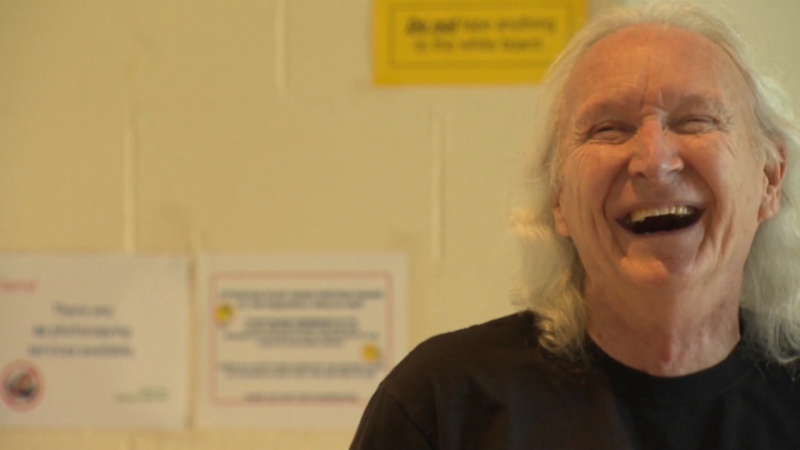

At the same time de Jong announced that former B.C. Appeal Court justice Wally Oppal would lead the inquiry, he announced a national consultation will be handled separately by the Native Women's Association of Canada. It will look into issues such as drug addiction, poverty and lack of access to social services that allow women to become marginalized.

The First Nations group Sisters in Spirit has said there are 582 missing and murdered aboriginal women and girls in Canada. The group didn't put a time line on that figure.

Nicholson said the latest federal budget has $10 million allocated to the issue of murdered and missing aboriginal women and an announcement around that would be made soon.