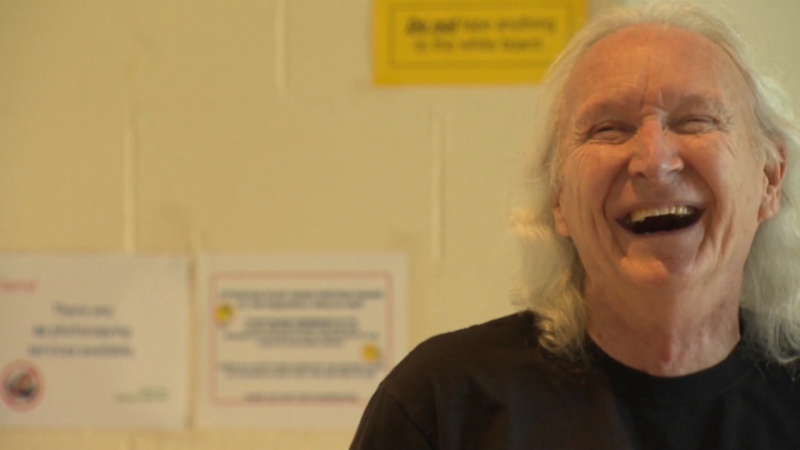

VANCOUVER -- Daniel Robert Krinbill has lived a hard life.

Krinbill endured years of childhood trauma, suffers from dissociative identity disorder and has faced a series of life-threatening medical issues.

Now, the 57-year-old says he's had to fight for an important medical procedure because doctors didn't want to proceed while he was under a Do Not Resuscitate order, the kind that prevents health workers from performing CPR should a patient go into cardiac arrest.

"I feel like I’m being manipulated based on my psychological history," said Krinbill through tears. "All I want is the same rights as everybody else."

The patient told CTV News his latest medical issues were detected during a recent CT scan, which uncovered an abnormality in his heart.

"They found a dark spot in my lower-left ventricle that they feel is a blood clot," Krinbill explained.

It was an alarming discovery considering he was already taking blood thinners for deep vein thrombosis in his leg. He was admitted into Abbotsford Regional Hospital a few days later and told he was in need of an angiogram, which involves inserting a catheter close to the heart and releasing a dye that makes one's blood vessels visible via X-ray.

Krinbill was told he'd be taken to Royal Columbian Hospital for the procedure then returned to ARH for recovery – but the plan was quickly upended.

"I informed them that for procedures like that, I was Do Not Resuscitate," Krinbill said.

The patient told CTV News he's concerned about the damage CPR could do to his already frail body, but that he was given an ultimatum: drop the DNR or be discharged from hospital.

"They won’t touch me unless I remove the DNR even though they state there is no reason for me to have a DNR because nothing (seriously life-threatening) ever happens,” Krinbill said.

Initially, Krinbill said he was not given a clear reason as to why they couldn't honour his wishes, but was eventually told it was age-related – something he has trouble believing.

"It shouldn’t matter how old I am. I’m of age to make my own choices and I’m of sound mind," he said, adding that he believes his mental illness was a factor.

Fraser Health could not comment on the details of Krinbill’s case due to privacy concerns, but said his history of mental illness did not play a role in his doctor’s decisions.

Dr. Gerald Simkus, the chief of cardiology for the Fraser Health region, told CTV News it's "unusual for a patient to be so dogmatic about situations," but that doctors can decline to perform a procedure they feel is too risky.

“It’s a two-way street. The physician has to agree to do the procedure and a patient has to accept having the procedure done,” Simkus told CTV News.

Simkus said although angiograms are fairly routine, there are risks with any medical procedure.

“Anytime you touch the heart, you can have all the worst complications – stroke, heart attack, death, all that kind of stuff. Anytime a catheter goes up to the heart it can tickle the heart, trigger cardiac arrest,” he explained.

That’s why most doctors prefer having the option to take action if things go wrong.

“It would be considered a breach of a medical practice if you’ve caused a complication and you can fix it easily, not to fix it. So it’s a difficult ethical decision and a difficult legal decision,” said the cardiologist.

Simkus said because each case is unique, there are no black and white rules that always apply when it comes to DNRs.

CTV News reached out to Fraser Health for comment on Friday, but was told no one was available for comment. Hours later, Krinbill said several doctors came to his hospital room and asked him to not speak to the media.

Fraser Health would not comment on that claim.

Krinbill was also offered an alternate test, but was told it would not be as accurate as the angiogram. He refused.

A short time later, he was told a surgeon at Royal Columbian Hospital was willing to do the procedure with a DNR Code 1 in place.

The goal of a DNR Code 1 is to "reverse medical problems or sustain life, with transfer to acute care AND assessment for critical care interventions WITHOUT intubation. Non-invasive ventilation may be offered,” according to Fraser Health’s website.

Intubation and chest compressions would not be performed in that scenario.

Krinbill has agreed to those terms, thanking staff and ARH for being his advocate even though they will not be the ones doing the procedure.

However, he’s still frustrated, saying he feels it took the help of the media to get the options he’d asked for.

“Nobody tries to fix the problem, they just sort of label you and move you along,” he said, getting visibly emotional.

Krinbill is scheduled to undergo the procedure, with the new stipulations in place, on Monday at RCH.