Justice officials have turned increasingly to peace bonds to keep some of the country's most notorious offenders from reoffending, a practice critics say is a recipe for an offender's return to prison and a constitutional challenge.

Every year in Canada, hundreds of peace bonds are issued against some of the country's worst offenders under Section 810.1 and 810.2 of the Criminal Code.

"The attorney general decided that we didn't want to take the risk of them falling through the cracks,'' said Det. Judy Dizy, the administrator who gathers evidence against alleged offenders facing Section 810 hearings in British Columbia.

"You know, all they need is a week or two and they can disappear in our country.''

Dizy will gather with other law enforcement officials from across the country starting Monday at a criminal justice conference in Abbotsford, B.C., on reducing the impact of dangerous and prolific offenders on public safety.

British Columbia is the only province that has a centralized system for peace bonds.

Fifty-four of the bonds were granted in B.C. last year, while Quebec judges granted 78 bonds from both sections of the Criminal Code and Manitoba had 12 peace bond applications.

While Ontario prosecutors do ask for peace bonds, that province doesn't keep track of how many of the bonds are approved.

Section 810.1 targets people who police fear may commit sex offences against children under 14 years old, while section 810.2 involves those who may commit a serious personal injury offence.

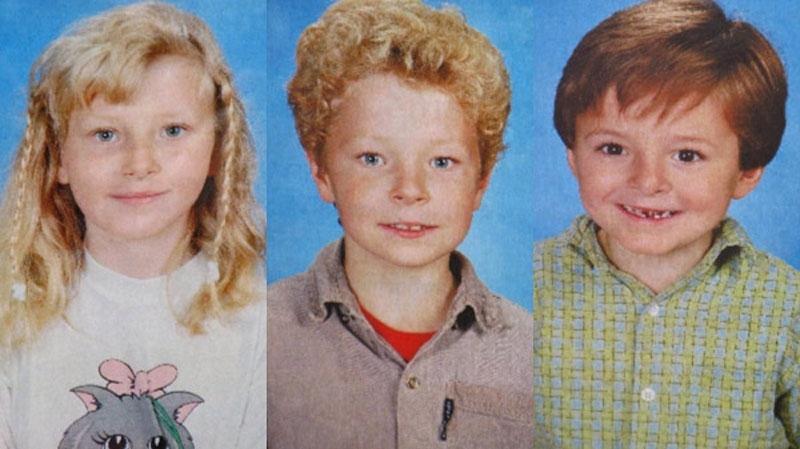

Authorities attempted to monitor schoolgirl killer Karla Homolka with such a peace bond, but a Quebec court lifted the restrictions weeks after they were imposed when she was released in June 2005.

Accused pedophile Orville Mader, who is wanted by Thai authorities on charges of assaulting a boy, is also living in B.C. under an 810.1 order, even though he faces no charges in the province.

The most notorious of recent 810 inductees is the man known as the Balcony Rapist. Numerous conditions were placed on Paul Callow before he was allowed to live with his sister in Surrey, B.C.

Most of these offenders, including Homolka and Callow came out of prison at the end of their sentences and had no parole conditions to meet.

"There's a Constitutional argument to be made around the notion that it is post-sentence punishment,'' said Jason Gratl of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association.

"Because of the low threshold required to restrain the liberty of an individual, these are easily subject to abuse. They require wise and careful decision making on the part of the judge.''

Because they face no parole requirements, the offenders also have no support system from government and the groups who help former prisoners are already stretched for resources.

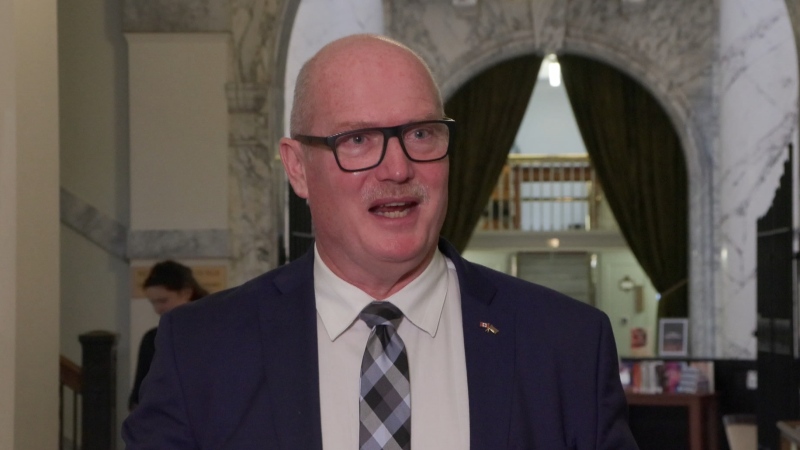

"I think it could be a lot more effective if there were more support programs that were put in place,'' said Tim Veresh, the executive director of the John Howard Society in B.C.

Those released on section 810 bonds have as many as two dozen conditions to follow when they're released by the court, including staying off the Internet or away from where children might play.

Veresh said someone caught breaking a condition under an 810 order can be picked up, but that hasn't been tested in court and is rarely done, so that person actually has to be caught breaking the law.

"Which means we have to create another victim,'' he stated.

"There's a few fallacies, I guess, with an 810 order that the public believes it makes them safer.''

Karen Bardach, Callow's sister, said the peace bond has prevented her brother from getting on with his life, going to school and leaving the province last year to see their dying brother in Edmonton.

"How do you go and reconcile with a dying brother after he's died? You can't.''

She said justice officials don't want to see the problems with law or why it needs to be changed to support these people.

"To me, it was like they were doing everything (they) could to make sure he fails.''

Callow lives with his sister's family in Surrey, B.C. and is working for her TV production company.

Glen Flett of the group LINC, or Long Term Offenders Now in the Community, said an offender has far more advantages coming out of prison on parole than being shackled with an 810 order.

"We need to help these people a lot more with resources like psychologists, like mentoring programs, like housing, like jobs,'' Flett said. "Not to just supervise them but to actually connect them in.''

He said if they don't get immediate help, often by the time the offenders get some help they've done something they shouldn't have.

Flett, who faces a lifetime on parole for murder, said pushing someone out of prison on parole is far safer for the public and the offender.

He said 810 orders are more of a political solution than they are practical.

"It sounds good don't it? We're protecting the public because we've got them on 810 orders. Well what does that mean?'' he said. "I've seen guys violate their 810 order and take six months to get into court before they actually get any resolve on that happening.''

Dizy said the offender is given the support of a probation officer and referred to groups that can help them but Flett disputes the claim of support.

"These guys don't have jobs when they get out. So what are they going to do?'' he said. "You know how many guys that get out of jail that are on 810 orders and they have $80 in their pocket and no place to live? It's unbelievable.''