VANCOUVER -- As they target a notorious organization tied to shootings and the drug trade, B.C.’s anti-gang agency says gang-related killings and attempted killings have taken a nosedive in part due to a new analytic tool they’ve revealed for the first time.

Over a two-year period starting in December of 2017, the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit has seen a 38.5 per cent drop in attempted and successful gangland killings — a time period that overlaps almost directly with their scrutiny, analysis and hassling of the Brothers Keepers.

The CFSEU has been harrying confirmed and suspected gang members with 259 interdictions since early 2018, ranging from traffic stops to ind-depth investigations, but they’ve also fully embraced social network analysis to keep up with shifting loyalties and alliances.

“One of or analysts has been really able to use that tool and really give us that in-depth scope and identify the individuals that really were responsible for a lot of the violence we were seeing on the street and give us that ability to really focus in and target on them,” said spokesperson Sgt. Brenda Winpenny. “It’s enabled us to really focus in and target on this group and really disrupt and suppress their criminal activity.”

Social network analysis has been used by everyone from marketers to political campaigners to public health officials to find the connections between people for years, but the scale of the Brothers Keepers analysis is unprecedented in B.C. and marks the first time law enforcement has publicly acknowledged using the system.

CFSEU’s work in this area was largely informed and guided by an SFU criminologist who’s been consulting with the organization for several years, and says there’s nothing predictive about it — it’s more of a high-tech and sophisticated version of the strings and photos popularized in crime dramas and movies.

“It’s not like an algorithm, there’s no modelling per se, but it’s saying let’s take the data together and organize it, try to understand it,” explained Martin Bouchard. “Once you organize it, it starts to make sense.”

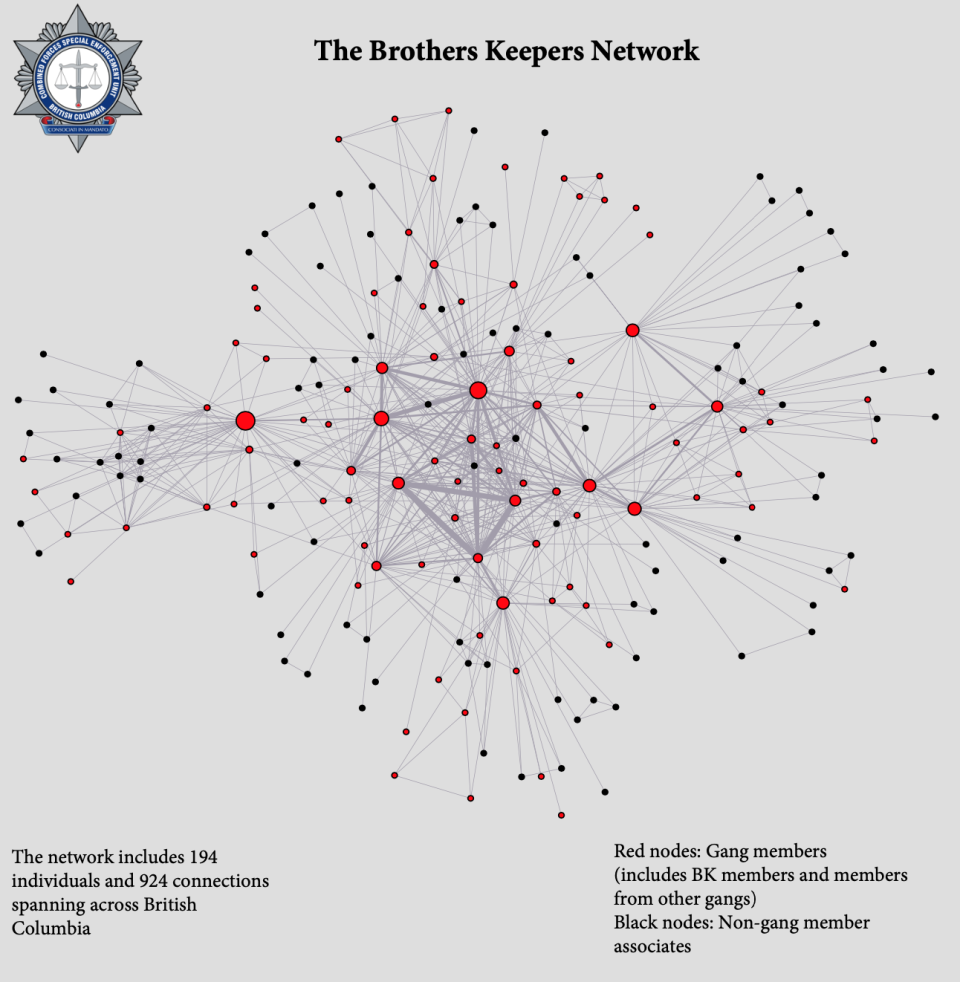

With about a dozen people believe to be the core members of Brothers Keepers, social network analysis pegs their network at about 194 people and “924 connections” across British Columbia.

Who’s who in the zoo?

Getting on the chart of contacts is actually quite complicated. In the same way a quick look of your Facebook friends list can’t tell someone which people are your close friends versus casual acquaintances, investigators can’t assume everyone who’s been in contact with a Brothers Keeper is a criminal associate.

“It’s most probably a network of police interactions, so interactions between people as seen by the police in one capacity or another, so if these people are under surveillance, if they’re seen waking together into a coffee shop, a restaurant, there’s the first clue,” said Bouchard. “When we first started looking at this, my colleagues and I, including (in) Montreal where I originally come from, would have access to wiretaps, so you have the phone calls between people. So a call from one person to another becomes a link in the network but 99 per cent of the phone calls in any investigation would be not part of the investigation. So these calls are normally dropped from the analysis.”

It takes a tremendous amount of intelligence work on the ground as well as analysis to make those links while dropping others, but the gang became a big priority for the CFSEU, with massive drug seizures and murders tied to the group in recent years.

“The Brothers Keepers first emerged within the British Columbia gang landscape in 2017 and were immediately in direct conflict with rival gangs such as the Red Scorpions, the Wolfpack, the Hells Angels, the United Nations, and numerous other individuals and groups,” said a CFSEU press release on the Brothers Keepers task force. “This conflict resulted in violence manifesting on streets and in communities across the province.”

A tool with many uses

Bouchard describes violence as a social contagion, with murders and similar crimes closely tied with those who know each other.

“You can follow a victim’s networks and build a network around them prior to the shooting and you sort of discover this social contagion effect — that conflicts stay close to you, close to the people you’re with,” he said. “You don’t shoot a stranger — it’s an enemy, someone you’re competing with for turf or for a piece of the pie.”

And while social network analysis can lead investigators to those they hadn’t realized were involved with violent actors, it can also warn those who have no connection to the violence to steer clear.

“You have a duty-to-warn aspect where you can tell these people ‘you may not know this, but you’re very close to people in an intense conflict right now and you can find yourself in the crossfire,’” explained Bouchard.

“This is the single best use of network analysis that I know, from a victim and victimization point of view and duty to warn as the main objective.”