As Jessa Turner sorts through donated Christmas items in her bright garden-level suite in Coquitlam, she motions to a tiny plastic Christmas tree tucked into a cardboard box on the ledge of her fireplace. She explains that she started this drive with the Coquitlam homeless shelter four years ago, when she spent the holidays alone because her children were with their father and she’d finally cut off contact with her parents.

Turner, who was previously known by her legal name Janet Hasenknopf, says the Christmas drive goes to show that people who have been through as much as her can still help their communities.

"I've busted my ass," she said. "I was pretty much seen as a lost cause… It was impossible to be a self-advocate in the mental health system.”

When people hear Turner's story of her mental illness, they're usually shocked. She says her post-traumatic stress disorder and dissociative identity disorder were originally misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder. She says that misdiagnosis came with serious consequences, including unnecessary shock therapy and over-medication. Now, she's calling on health care providers to listen to patients and pay more attention to childhood trauma.

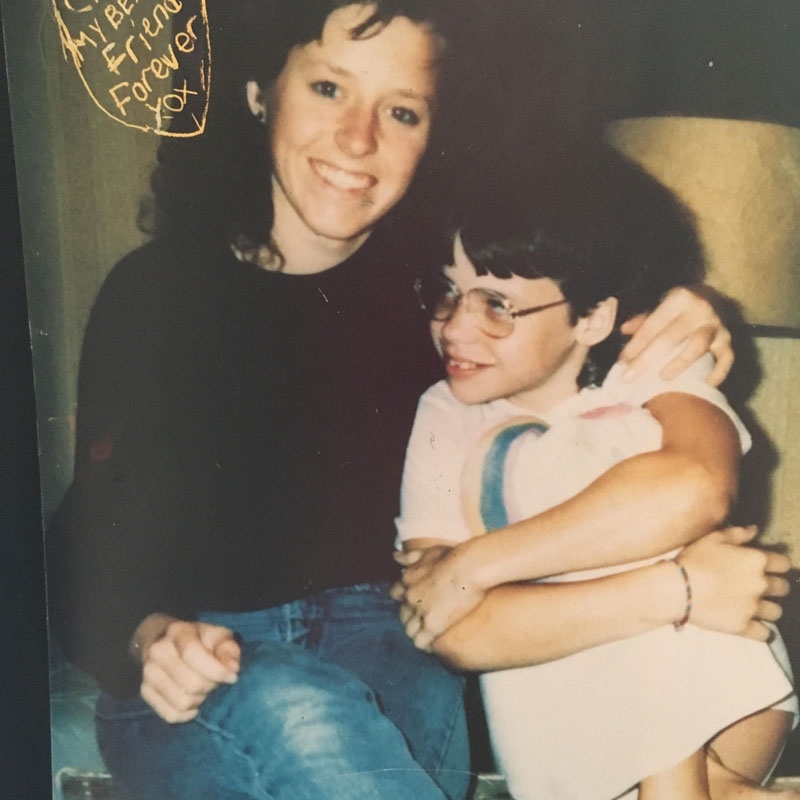

Turner is 39 now, but her saga starts when she was 11. That's when her older sister, a 19-year-old University of Victoria student, killed herself.

Turner is pictured here with her older sister in February 1990, three months before her sister died.

By 12 and a half, Turner was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital for depression and suicidal ideation. That began a near-decade of Turner being in and out of various Lower-Mainland hospitals for mental health issues.

A turbulent decade

In Turner's medical records from 1994, when she was 15, doctors and nurses describe how she would call the crisis line saying she was going to kill herself and be taken to the hospital by ambulance. Turner says it was too hard living at home and saw the hospital as a way to escape.

"My coping mechanism before used to be to go to emergency. I thought that's where I belonged," she said.

Turner was first admitted to hospital for mental health issues just before she turned 13.

Some time later, she received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. She was put on medication that she says made her feel like a "zombie." She remembers when she told staff that she didn't want to take the pills, they told her she had to.

"I repeatedly said I didn't need the medication and I was told that was denial and that was the number one symptom of bipolar," she said. "I vividly remember that. I remember hearing that and just feeling trapped."

She thinks if someone had listened to her earlier, she'd have saved a lot of time in her recovery.

Turner explains she'd like to see mentally ill patients listened to.

Turner explains she'd like to see mentally ill patients listened to.

Turner says she was certified under the Mental Health Act several times because of her suicide risk. This piece of legislation allows patients who are at risk of harming themselves or others to be held in hospital and forced to take treatment.

A statement from the B.C. Ministry of Health explains that certified patients have the option of applying to a review panel. They can state why they don't feel they need to be hospitalized or undergo a certain treatment.

Turner says she may have been presented with this option, but thinks she was in too much of a medicated haze to realize it might make a difference.

Shock therapy for bipolar disorder

When Turner was 20, she got married. She had three kids and lived medication-free for seven years.

But in 2007, when she was 29, she left her marriage. She says she was devastated when her ex-husband got primary custody of their children. She attempted suicide again and ended up back in hospital on medication for bipolar disorder.

In 2008, she says she was even subjected to electric shock therapy.

"They made me sign for it... they said if I didn't they were going to do it against my will," she said.

By doing it against her will, Turner meant she'd be certified.

Electroconvulsive therapy is an evidence-based treatment administered in B.C. under strict guidelines, according to the B.C. Ministry of Health. It's recommended for use with major depressive episodes, acute suicidality, mania and schizophrenia. It is not recommended, however, for use with anxiety disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder.

A recent report by the Community Legal Assistance Society said B.C.’s Mental Health Act sometimes violates patients’ charter rights by putting them in solitary confinement or giving them involuntary treatments like ECT.

On top of her mental health issues, Turner developed spinal stenosis--a degenerative narrowing of the spinal column that puts pressure on the nerves. She says she woke up one morning and couldn't walk. She needed surgery.

That's when she met a psychiatrist who changed her life.

Turner needed to have several surgeries that fused her spinal column between 2009-2011 after developing a degenerative condition called spinal stenosis.

Bipolar disorder a misdiagnosis

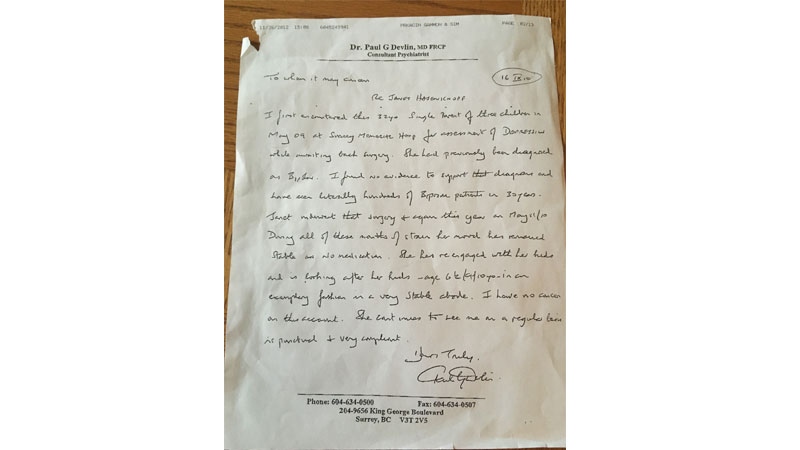

While waiting for her surgery, Turner met Dr. Paul Devlin, who at the time was head of psychiatry at Surrey Memorial. He is a physician with more than 30 years of experience practicing psychiatry. After evaluating her, he said bipolar disorder seemed like a misdiagnosis.

"She didn't meet the criteria for bipolar disorder," Dr. Devlin told CTV News. "[She was on] the right medication for the wrong diagnosis and it was affecting her adversely. And she felt terrible."

Dr. Paul Devlin wrote this letter for Turner saying he found no evidence to support a bipolar disorder diagnosis.

After years of telling health care staff she didn't need medication, Turner finally felt validated.

“All of these things happened... I was certified. I had ECT. I was over-medicated. And at the end of the day I was misdiagnosed," Turner said. "I think that's part of why I'm feeling so passionate about the whole thing now... nobody heard me."

Mental health diagnoses are subjective

Changing diagnoses or multiple diagnoses at once do happen in mental health care, says Emily Jenkins, a nursing professor at the University of British Columbia.

"Unfortunately, with mental health disorders there is no laboratory test that we can use to diagnose," she said.

Instead, health care providers use their own observation and what patients tell them in interviews or on questionnaires to compare against disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

A spokesperson for the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health said CAMH does not track data on misdiagnosis and that he was not aware of any such database.

"It's not even a certainty that someone who improves without medication means they were misdiagnosed," said Sean O'Malley.

The B.C. Ministry of Health advises that patients concerned about inadequate or inappropriate treatment "should feel free to openly discuss these issues with their physician." If that conversation is unsuccessful, the ministry says patients can file a complaint with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C.

Turner started painting while awaiting her surgery at Surrey memorial.

Since her back surgery, Turner has been working with a psychologist who thinks she's most likely suffering from complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Dissociative Identity Disorder. The latter is a condition that's usually caused by physical or sexual abuse when patients are children. Dissociation is used as a coping mechanism by the child to deal with overwhelming scenarios.

In particular, Jenkins says PTSD and bipolar disorder can look similar.

"Sometimes the sleep disruption [associated with PTSD], for example, can lead to some of that agitation. And that could mimic a hypomanic episode," she said.

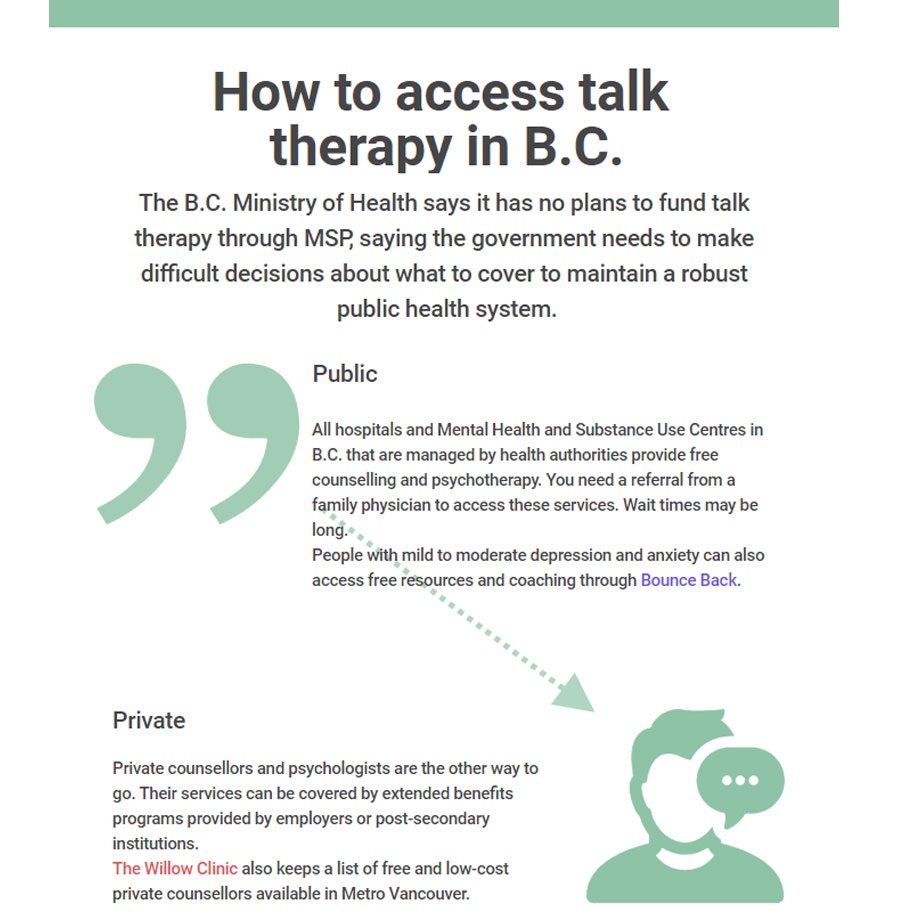

Talk therapy helps, but it's expensive

After Turner's back surgeries, she turned to a private counsellor to work on her dissociation and PTSD. She says it's been expensive, eating up $400 a month of her disability income, but incredibly helpful.

"I think the proof is in the pudding, so to speak," she said. "To go from being heavily medicated and in the revolving doors of the hospital to being able to be functioning, dealing with life…"

Jenkins says she'd like to see the province prioritize a more comprehensive approach to mental illness.

"One of the injustices in the current way that our mental health care system is structured is that physician and hospital services are free to us but psychotherapies are often not," she said. "That leaves a lot of people without access to appropriate counselling or psychotherapy services."

Six years of counselling later, Turner is doing better than ever.

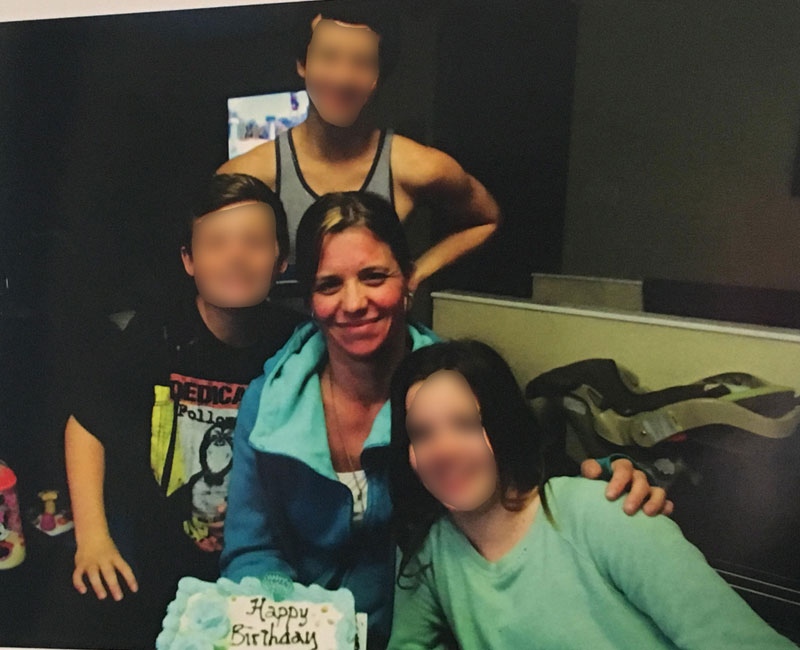

She's regained custody of her children, and her youngest lives with her in her Coquitlam apartment. She works part time as a house cleaner and has started her own business selling her paintings online.

Now that she's overcome so much, she wants to advocate for change so that her experience won't be in vain.

"I think that people need to hear the reality of the system," she said. "And the fact that not everybody in the mental health system is a lost cause."