VANCOUVER -- In the aftermath of arrests and protests over a planned pipeline in northern B.C., the roles of elected and hereditary chiefs in the province's Indigenous communities is being scrutinized.

The elected chiefs of the Wet'suwet'en First Nation had agreed a deal with TransCanada, now known as TC Energy, that would allow the Coastal GasLink project to run through their territory in 2014. The 670-kilometre, $6.2 billion pipeline by Coastal GasLink would carry natural gas from the Dawson Creek and connect it to LNG Canada's natural gas operation in Kitimat.

But the deal has faced opposition from some hereditary chiefs – also known as house chiefs in the territory as they represent different houses that make up the First Nation as a whole - and some members of the nation, leading to the creation of a protest camp that blocked access to CGL's intended worksite near Houston, B.C.

"The Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs have never consented to the Coastal GasLink pipeline project and been actively opposed to it since its inception. The project will threaten Wet’suwet’en territories, society, culture, governance system, and the stewardship responsibilities of the Chiefs," the band wrote in a December press release.

But do both the elected chiefs and the hereditary chiefs speak for the group as a whole? Or does one take precedence?

Elected chiefs

Elected chiefs were created out of the Indian Act of 1876 by colonialists who came to North America, seized Indigenous Land and attempted to put their own system into place.

The act created the elected chief and council system. These representatives are subject to elections held every two years.

"It's incredibly simple," says Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, with the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs when asked about the differences. "Band councils have authorities, powers and jurisdiction on the reserve land base itself. And where the border of the reserve ends, so ends their power and jurisdiction."

Professor Sheryl Lightfoot, the Canada Research Chair in Global Indigenous Rights and Politics and an associate professor, First Nations and Indigenous Studies and Political Science at UBC, echoed Phillip's comments, saying the confusion between the two often comes from a lack of knowledge.

"People don't know much about the Indian Act, that's the core problem," she says, adding the Act isn't well taught in the Canadian education system.

Hereditary chiefs

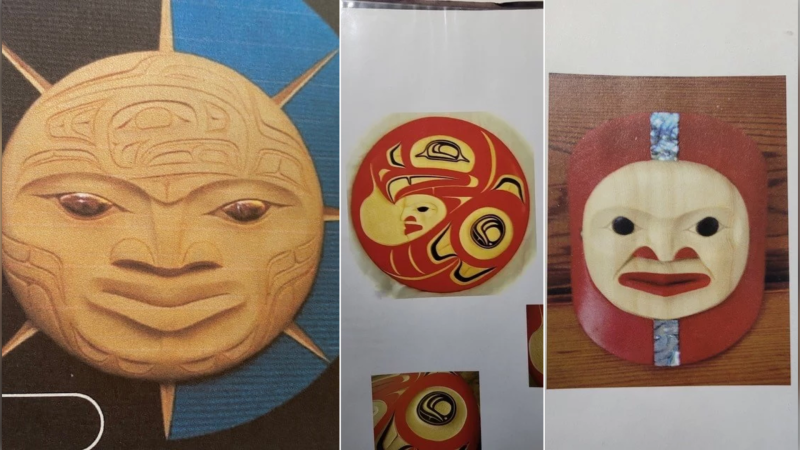

Hereditary chiefs are a title passed down through families. They hold a position of influence in a community where the title has been handed down between generations.

Who it's passed down to can vary between nations, depending on their history. Some follow a patriarchal system while others follow a matriarchal one.

Adding a layer to that, some hereditary leaders run for an elected office meaning they represent both sides.

The hereditary role is seen as focusing on protecting the territory, and doesn't just include economic factors.

"Hereditary leaders have responsibilities. When we talk about traditional leadership, it's much heavier on responsibilities than it is on authority," says Lightfoot. "Hereditary leadership goes back to time immemorial, and it is intrinsically tied to a territory and the land."

Lightfoot says there's a tendency to view hereditary leadership roles through asking what powers they have. Instead, she says their role should be viewed through a more holistic lens.

Roles can lead to differences

Not every Indigenous community has a hereditary chief or chiefs, but those that do can see divisions of opinion between the two forms of leadership.

"They can get along really well, or they can fight like the Hatfields and McCoys," says Bob Joseph, a hereditary chief of the Kwakwaka’wakw group of nations.

Joseph says he views his role as largely a spiritual one, but with a focus on helping those in the community.

"My dad is a hereditary chief and our responsibility is to the people. Everything we have to do is for the people," he said.

The issue of hereditary rights versus elected band councils is particularly contentious when it comes to the Wet'suwet'en First Nation.

The group was part of Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, which is seen as a ground-breaking case in Canadian law and Indigenous rights that upholds Indigenous peoples' claims to lands that weren't ceded by treaty. Much of B.C. is unceded territory, with a slate of unresolved land claims and debates.

What comes next is anyone's guess, but in a perfect world, experts say the two sides work as a unified force in Indigenous communities.

"In an ideal world, the elected council would consult with the hereditary council before making any decisions as part of their own community consultations. That's the best case scenario," says Lightfoot.