B.C. toxic drug crisis: Fewer 911 calls as deaths continue

BC Emergency Health Services saw a slight decline in 911 calls for overdose and drug toxicity last year, but some areas saw a dramatic increase, and the death rate doesn’t appear to be slowing down.

Province-wide, there were 33,654 calls last year, which was a five-per-cent decrease from the year before. It’s the first time since 2016 that the number has gone down; prior to the toxic drug crisis, call volumes fluctuated between 10,000 and 15,000 per year.

“It's a very critical call to deal with and you really do need all hands on deck,” said BC EHS communications officer and veteran paramedic Brian Twaites.

“These patients are unconscious, they're not breathing, so that's a real emergency and don't hesitate to phone.”

While Vancouver and Surrey both saw reductions of 22 per cent, Victoria saw four per cent more, Kelowna rose 15 per cent, and Abbotsford saw a 20 per cent spike in calls for help with overdoses or toxic drug consumption.

DEATH RATE NOT DECLINING

The numbers are jarring considering B.C. is on track for another record year of drug-poisoning deaths.

One of the province’s most prominent drug analysts says the years-long campaign to provide and train people in the use of the overdose antidote, naloxone, is starting to have a big impact in urban areas.

“People helping each other is making the biggest difference,” said Karen Ward. “It’s difficult to think about how you could intervene … make sure someone you trust knows you’re using.”

The BC Coroners Service regularly provides information about where people are dying from illicit drug toxicity, and the data hasn’t changed: slightly more than half of all deaths are in private homes, with roughly a quarter in group living settings like supportive housing.

On Monday, federal government representatives will join with their provincial counterparts to discuss the decriminalization of several illicit drugs this week – a move intended to curb the death toll and widely supported by health-care professionals and police.

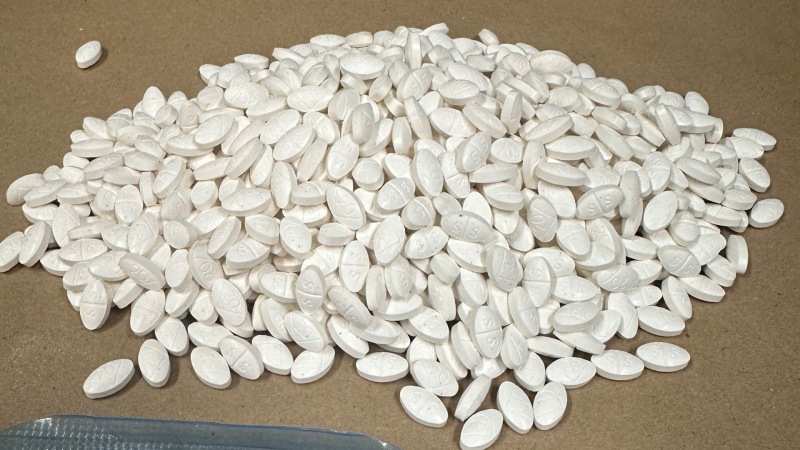

DRUGS CHANGE QUICKLY, THE RESPONSE DOESN'T

When CTV News spoke with Ward in Gastown, she noted the toxic drug crisis had been running for 2,481 days and the drug supply has only become more unpredictable and volatile. She described it as “a toxic soup of random chemicals.”

More than 10,000 people have died in those years, and the province has appointed a minister of mental health and addictions to show its commitment to helping people. At the same time, however, it has struggled to ramp up the availability of treatment options, safe supply, and the housing that advocates and researchers repeatedly insist is the foundation for a healthier lifestyle that’s more conducive to recovery.

When CTV News pointed out that the drugs change a lot faster than the strategy to respond to them, Ward agreed and added that even the symptoms of overdose have changed based on the most prevalent drugs in each wave of the crisis.

“There is a need to be able to adjust and adapt really quickly, but we're not addressing it in a timely, emergency-oriented way,” she said.

Both Ward and Twaites reiterated the best ways to survive an encounter with toxic drugs: avoiding using alone, having naloxone handy, testing drugs if possible, and even using an app as a backup.

“Always call 911 if you see someone who you think is having a drug overdose,” said Twaites. “Our call-takers can walk you through those steps of giving naloxone, maybe they need chest compressions for cardiac arrest – they can teach you how to do that over the phone while fire department, first responders and paramedics are being dispatched.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Man sets self on fire outside New York court where Trump trial underway

A man set himself on fire on Friday outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump's historic hush-money trial was taking place as jury selection wrapped up, but officials said he did not appear to have been targeting Trump.

BREAKING Sask. father found guilty of withholding daughter to prevent her from getting COVID-19 vaccine

Michael Gordon Jackson, a Saskatchewan man accused of abducting his daughter to prevent her from getting a COVID-19 vaccine, has been found guilty for contravention of a custody order.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

The Body Shop Canada explores sale as demand outpaces inventory: court filing

The Body Shop Canada is exploring a sale as it struggles to get its hands on enough inventory to keep up with "robust" sales after announcing it would file for creditor protection and close 33 stores.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

On federal budget, Macklem says 'fiscal track has not changed significantly'

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem says Canada's fiscal position has 'not changed significantly' following the release of the federal government's budget.