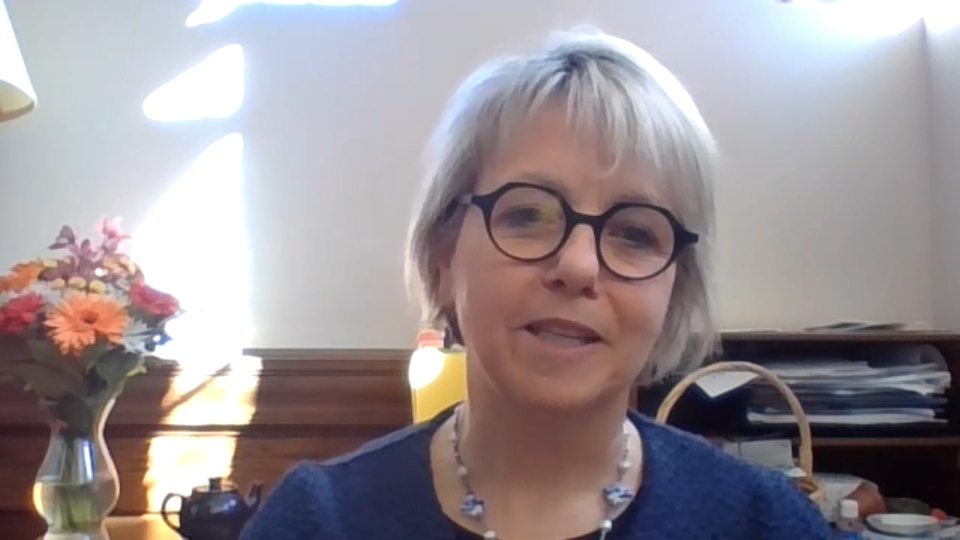

Watch the full one-on-one interview with Dr. Bonnie Henry above.

VANCOUVER -- Almost a year to the day since the last time I'd been in a room with B.C.'s provincial health officer, I was facing her through a computer screen for a virtual one-on-one discussion on the 365 days since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic.

Dr. Bonnie Henry was sitting in her office in Victoria as we dove into the questions I'd prepared. Initially, I wrote out more than two dozen questions I felt were urgent or important to address, but narrowed it down to five (and two "just in case there's time") because the media relations staffers had only given me 15 minutes with her; I ended up taking 20.

We talked about care homes, and why after a year, and so many vaccinations, there were still outbreaks and strict limits on visitors. When it came to schools, I asked whether she'd been to any classrooms to see her orders in practice (yes, several, she said) and she bristled when I brought up a Canadian epidemiologist's concerns B.C. is "courting disaster" by not doing more to address COVID-19 variants in schools.

You'll have to watch the interview for her comprehensive answers to those issues and my queries around vaccine confidence.

But what really struck me was how candid and self-reflective she was on what she wishes she'd done differently and how she feels public heath communication could be improved.

"There's a sense of uncertainty we've had this whole year, and when we learn more and we understand from the data about what's happening and we change things, that can become very difficult for people. It can be confusing and we know that," she said when asked about her regrets.

Her tone was honest and she replied with what felt to me like a genuine desire to have her process understood. When I asked whether it was fair to describe her approach as preferring to stay the course, even if imperfect, rather than upset the apple cart, she agreed.

"I hear from a lot of people that change leads to confusion. And we're trying to have as minimal restrictions as we need to get us through the phases we've been to, and to appeal to people to understand the spirit of the restrictions, rather than putting things on and off and on and off," said Henry. "We've seen that in other jurisdictions and that can lead to even more confusion and frustration and people aren't sure what the right thing is."

The question I most wanted answered turned out to be the one that was perhaps most vague.

Last year, I was one of several reporters who asked her to reveal B.C.'s possible COVID-19 fatality rate, as the federal government and premier of Ontario had done. I was politely, but firmly, rebuffed. One year later, I decided to ask how many lives she thinks had been saved as a result of the many sacrifices people have made, and the heartache that's resulted from keeping apart to avoid viral transmission.

"People in British Columbia have understood the spirit of the orders of the restrictions, of what we've been trying to do here, and it has saved thousands of lives," she told me. "Everybody acting as an individual means collectively we have been protected."

It's not what I was looking for, but it was still nice to hear that affirmation after a difficult year.