VANCOUVER -- With British Columbians poised to start leaving their homes more often and risking exposure as COVID-19 distancing measures are relaxed in the next few weeks, the province’s top doctor revealed her staff has been quietly testing apps that could help people identify when and where they may have been near people carrying the virus.

CTV News asked Dr. Bonnie Henry Tuesday if she was working on an app-based approach to contact tracing, similar to what Alberta rolled out over the weekend.

“We’ve been trialing some apps to assist in that, particularly if we identify a case and we identify their contacts, being able to connect with them and use some of the information around where they’ve been and who they’ve been in contact with,” revealed Dr. Henry. “We’ve been looking into this a lot, we need to find the right IT support for the work we’re doing — that doesn’t create more problems than it solves.”

Chief among the concerns are protecting users' privacy and ensuring the efficacy of the technology outweighs the risks and issues associated with it.

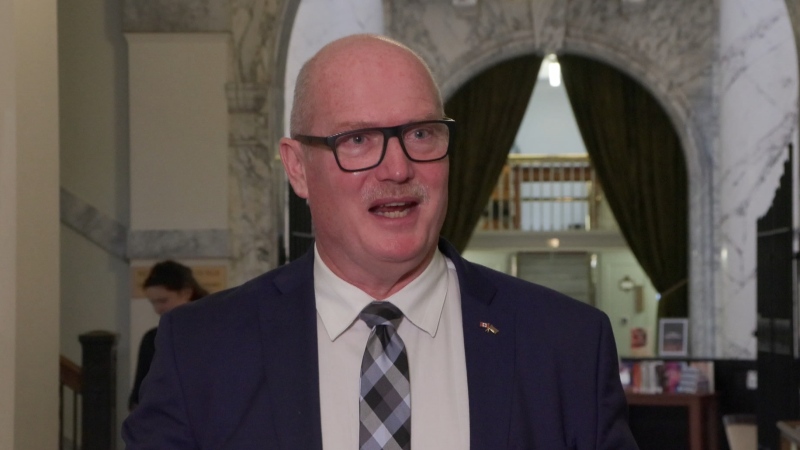

“Its sole purpose can only be ... getting the virus to be eradicated,” insisted B.C. Privacy Commissioner Michael McEvoy, who confirmed his office has been in discussions with public health officials working towards a publicly-available app.

“That’s a big issue, because I think if the public has a sense that it could be used in any other way — could be available, for example, for law enforcement purposes — people won’t download it and this has been an issue globally.”

Traditional contact tracing requires public health officials interviewing people who’ve tested positive for COVID-19 to determine who they’ve been in contact with — the goal being to both determine where the person was infected and notify those who may have been exposed so they can self-isolate. It’s time-consuming and relies on how much people can remember about their movements.

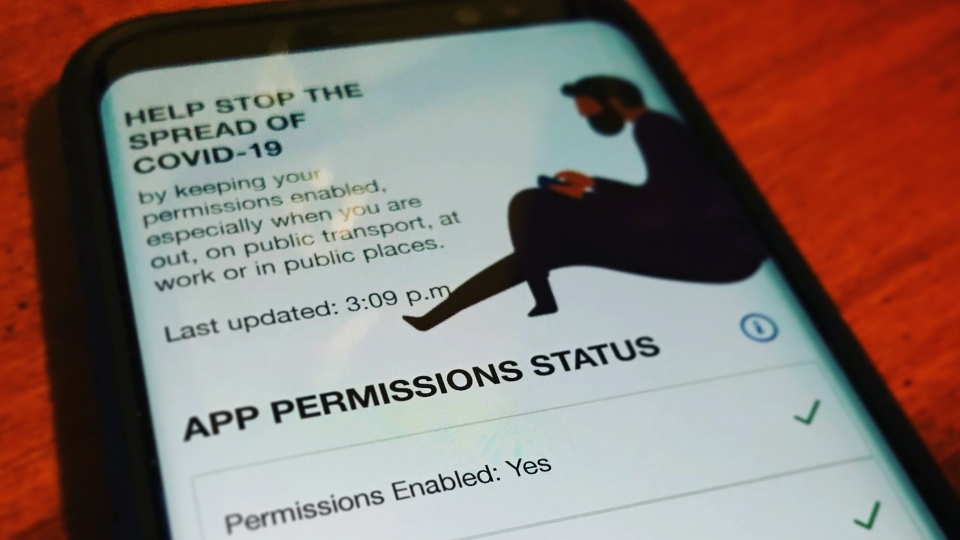

Alberta’s contact tracing app, AB TraceTogether, is a modification of Singapore’s app, which relies on Bluetooth to make anonymous “digital handshakes” with other users so that if they test positive for COVID-19 they can anonymously notify others they’ve been within two metres of for 15 minutes or more. The app has also been criticized for requiring iPhone users to keep their phone open and unlocked with the app running, otherwise it won’t collect data.

McEvoy points out that Singapore only has a 17 per cent participation rate, while public health officials say upwards of 50 per cent is required to have a positive impact.

“Without public trust of an application of this kind, it is not going to work,” he said. “Because it’s voluntary, it depends on people’s confidence in the system and if government takes steps to ensure it does protect people’s personal information it has potential to absolutely help the public health officer.”

Private companies may be next to implement apps

Vancouver tech startup Liv Nao has a decentralized notification system and says while they contacted numerous provincial governments and federal officials, the bureaucracy is taking too long and they’re now finding that private companies are most interested in using the contact tracing app for their workforces.

“We’re talking to industries that really need to get back to working — things that support our economy like manufacturing and construction,” said CEO Daniel Leung, noting that there’s no centralized dashboard to their app for employers or government to look up who’s reported a positive COVID-19 test result.

“When you say ‘contract tracing’ people immediately think Big Brother, but the thing is we can’t track people individually and we don’t share that information with the government,” he explained. “We can’t even identify you because all the people look to us as an ID — so like A123, there’s no name associated to it.”

Users would then receive an alert from the app if another anonymized contact is positive.

However, the opportunity for anxiety induced from what could be many false alarms, not to mention the opportunity for swatting-style intentional false alarms, make self-reporting technology problematic.

B.C. waiting for the right technology

“Everybody and their dog has an app out right now,” said Henry with a smile, insisting that an app isn’t a silver bullet, even with widespread participation.

“We’re not clear that there’s any evidence, at least in our context, that having something on everybody’s phone giving them generic messages about where they’ve been or who they’ve been in contact with is what we need right now."

But just because she hasn’t found the right app yet, doesn’t mean Henry is giving up on the idea.

“We are absolutely working on this, including with our Provincial Health Services Authority and our IMITS experts that are amazing, looking at how we can augment the IT systems we’re using already rather than something new and different.”