B.C. family doctor shortage impacting 911 service and ambulance waits

Long waits for 911 response or ambulance support have been making increasing headlines in recent months, but frontline healthcare workers and administrators alike point to a significant issue making situation worse: the ongoing family doctor shortage in British Columbia.

CTV News raised the issue with both the union for B.C.’s paramedics and a spokesperson for the province’s doctors, who describe the primary care crunch as a key factor in increased hospital visits and the surge in requests for emergency healthcare that’s escalated as the pandemic has dragged on.

“What you’ve [identified] is a whole system that’s really under a lot of pressures: not having a doctor is putting a lot of pressure on the 911 emergency system, and when you’ve seen a doctor in the emergency department, there’s nobody to follow up with that so you manage after your acute situation,” said Ambulance Paramedics of B.C. president, Troy Clifford. “It’s not just about putting more ambulance paramedics into seats, that’s not the only solution – it’s the whole continuity of care.”

While some people have avoided or been unable to see a doctor and seen their condition worsen to the point they need urgent medical care, frontline paramedics also describe some people trying to game the system, believing if they call 911 and are taken to hospital in an ambulance they can see a doctor faster; instead they are triaged at hospital and wait behind more urgent patients, while paramedics wait to hand them over to overburdened hospital colleagues.

“It’s a trickle-down effect,” agreed president-elect of the Doctors of BC, Dr. Ramneek Dosanjh “It’s a primary care system that’s been in need of some healthcare reform for some time."

She pointed out that the same model of family medicine has been in place for decades and has not adapted well to changing demographics, healthcare needs and the desires of doctors. In British Columbia, family physicians bill the provincial government for their services and have to find and lease their own space, hire their own staff and source their own equipment and supplies; most spend many hours running their business and some have little desire to do so, preferring to solely focus on practicing medicine.

“This is a system that’s been overburdened, people have been overworked. The working conditions really need to be evaluated and looked at,” said Dosanjh, pointing out doctors are walking away from the intense workload and demands of family practice, negating the addition of positions at medical schools in recent years. “We need to make sure that the existing family doctors that we have, that we don’t lose them because I think with this pandemic and the current climate of health care system delivery is very complex and it’s very challenging.”

A LONG-RUNNING PROBLEM WITH QUESTIONABLE PROGRESS

By one estimate, 700,000 people in the province can’t find a family doctor but even those who have one are complaining they have to wait weeks for an appointment, or they can’t see a physician in person at all. Primary care doctors are being warned to resume face-to-face care while maintaining virtual appointments, but it’s a common complaint that in-person care is still in short supply.

But physicians themselves are also struggling, with a spike in the number seeking professional supports, including counselling services, in what’s a nation-wide crisis in the health-care workforce amplified by the pandemic.

“No question that COVID-19 has, of course, made things worse. As people have been working really round the clock now for months in the system,” said Canadian Medical Association President, Dr. Katharine Smart last month. “I think what’s clear is yes, we need more people, but that’s not the whole story -- we also need a system that lets people do their work in a way that they find sustainable.”

Dosanjh described the provincial government as receptive to doctors’ concerns but also emphasized their ongoing calls for a multidisciplinary approach to primary healthcare to meet the increasingly complex needs of an aging population and increasing attention to mental health.

“We need strategies where we can improve our primary care network and involve a team-based care approach where we can have more allied health professionals like our counsellors, social workers, nurse practitioners and nurses involved in more comprehensive care to deliver what the patients of today need,” she said, suggesting the days of the sole practitioner are over. “Other jurisdictions around the world, people are doing things a little bit more innovatively”

British Columbians who don’t have a family doctor can try to find one in their community through a provincial directory. Non-urgent medical issues, including speaking with a nurse, doctor or pharmacist, are facilitated through the free Healthlink BC 8-1-1 service, 24-7.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Doctors say capital gains tax changes will jeopardize their retirement. Is that true?

The Canadian Medical Association asserts the Liberals' proposed changes to capital gains taxation will put doctors' retirement savings in jeopardy, but some financial experts insist incorporated professionals are not as doomed as they say they are.

Something in the water? Canadian family latest to spot elusive 'Loch Ness Monster'

For centuries, people have wondered what, if anything, might be lurking beneath the surface of Loch Ness in Scotland. When Canadian couple Parry Malm and Shannon Wiseman visited the Scottish highlands earlier this month with their two children, they didn’t expect to become part of the mystery.

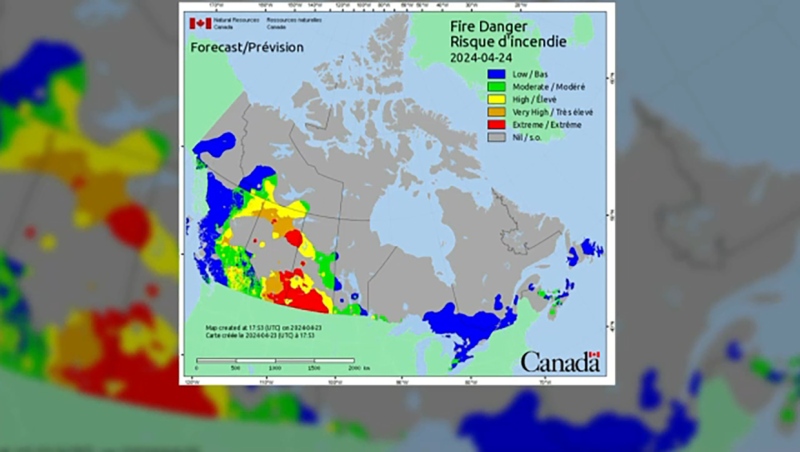

Fair in Ontario, flurries in Labrador: Weather systems make for an erratic spring

It's no secret that spring can be a tumultuous time for Canadian weather, and as an unseasonably mild El Nino winter gives way to summer, there's bound to be a few swings in temperature that seem out of the ordinary. From Ontario to the Atlantic, though, this week is about to feel a little erratic.

What do weight loss drugs mean for a diet industry built on eating less and exercising more?

Recent injected drugs like Wegovy and its predecessor, the diabetes medication Ozempic, are reshaping the health and fitness industries.

He replaced Mickey Mantle. Now baseball's oldest living major leaguer is turning 100

The oldest living former major leaguer, Art Schallock turns 100 on Thursday and is being celebrated in the Bay Area and beyond as the milestone approaches.

What a urologist wants you to know about male infertility

When opposite sex couples are trying and failing to get pregnant, the attention often focuses on the woman. That’s not always the case.

'It was instant karma': Viral video captures failed theft attempt in Nanaimo, B.C.

Mounties in Nanaimo, B.C., say two late-night revellers are lucky their allegedly drunken antics weren't reported to police after security cameras captured the men trying to steal a heavy sign from a downtown business.

Bank of Canada officials split on when to start cutting interest rates

Members of the Bank of Canada's governing council were split on how long the central bank should wait before it starts cutting interest rates when they met earlier this month.

Made-in-Newfoundland vodka claims top prize at worldwide competition

A Newfoundland-made vodka has been named one of the world’s best by judges at this year’s World Vodka Awards.