The authors of a new study are warning that Vancouver's affordable housing crisis is quickly spreading to the suburbs, leaving hard-working families teetering on the brink of homelessness.

The report, titled "No Vacancy," found that the once Vancouver-specific problem of high prices and low vacancy rates has reached as far as Surrey.

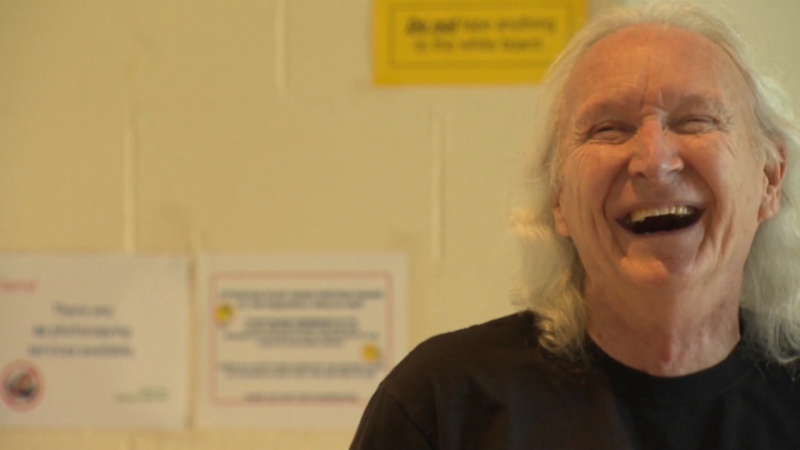

"Today's report shows that cities that were once seen as an affordable oasis are quickly sinking in high rents and low vacancy, and while no one is immune, it's absolutely hammering low-income families and women," said Jeremy Hunka of Union Gospel Mission, which co-authored the study with Penny Gurstein, a researcher at the University of British Columbia's School of Community and Regional Planning.

"Rents are way up, vacancy is way down, the crisis is spreading way out and homelessness is worse," Hunka said.

In Surrey, the second-largest and one of the fastest growing cities in the region, vacancy rates fell from 5.7 per cent in 2012 to near zero last year, the report said. New Westminster's vacancy was halved during that period, from 2.2 per cent to 1.1 per cent. The City of Vancouver already had a low 1.1-per-cent vacancy rate in 2012, which has since fallen to just below one per cent.

"We’ve been seeing this trend over a number of years, and we’re really reaching a boiling point," Gurstein said.

"Before, you could go into other communities like Surrey, Burnaby and New Westminster and find potentially affordable housing, but now the vacancies, as the report shows, are really low in those communities, so there really isn’t the kind of housing that is needed to fit the population."

At the same time, the cost of the few rentals that remain available has spiked. Data pulled from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation's Rental Market Survey shows rents have risen sharply across Metro Vancouver since 2012.

In the City of Vancouver, the average renter of a two-bedroom apartment pays nearly $2,000 a month, but even those willing to move out to Burnaby, New Westminster or Surrey are looking at well over $1,000.

"We see the human consequences at UGM every day," Hunka said, adding that the housing crisis is "disproportionately devastating women or single mothers who despite working hard are on the brink of disaster."

Jesse Kirkpatrick and Jackie Myerion have felt those consequences first-hand.

The couple and their two children were forced out of their Surrey suite by a landlord who they say wanted family to move in instead.

Unable to find another place to live, the family was forced to stay in a tent in Vancouver's Crab Park over the summer.

"Our daughter said it was just like camping to make it easier on her brother because he wanted to go home and we didn't have a home to go to," Myerion told CTV News.

It's a common story, according to researchers, who say the housing crisis has led to a 32-per-cent surge in the number of families on B.C.'s subsidized housing registry since 2014. More than 60 per cent of families on that list are led by a single parent—in most cases, a mother.

The report also shows that homeless shelters in the region have been operating at or beyond full capacity for the last five years.

And with so many people facing the possibility of ending up on the street, UGM is asking Metro Vancouverites to head to the polls with the issue of affordable housing in mind during the Oct. 20 municipal elections.

"The consequences are so dire that we're asking the public to vote with affordability in mind this election," Hunka said. "We believe this issue deserves special attention because lives are on the line."

UGM has also compiled a website with information about where mayoral candidates across the region stand when it comes to housing.

With files from CTV Vancouver’s Angela Jung