Ugandan brothers Wafula and Isaak are afraid of fishing in Lake Victoria after dark, and with good reason: their father died in a fishing accident six months ago, and a 16-year-old boy from their village drowned last month doing the same job. Neither wears a lifejacket and they only share one small headlamp to see their way on the water.

But both boys dropped out of school last month in order to support themselves, and their widowed mother.

“The money is too little,” Isaak said. “But we do what we have to survive.”

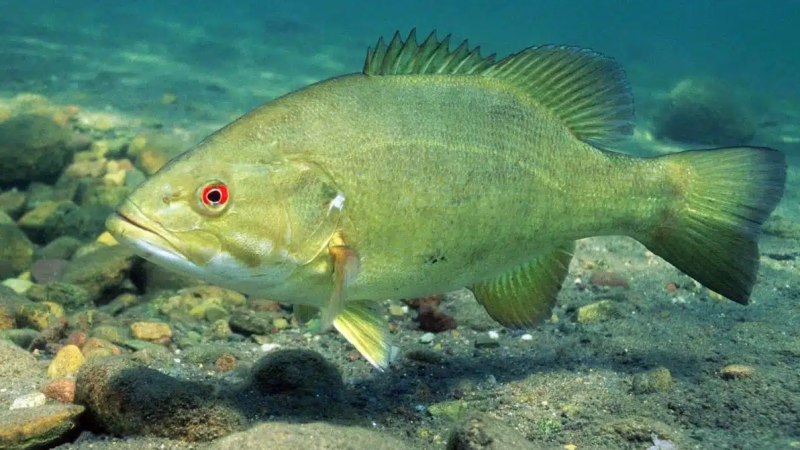

For six hours of fishing tilapia on the rickety boats, the boys will be paid between 2,000 and 3,000 shillings — around $1.

Their catch will not remain in the community. Instead, it is whisked away in refrigerator trucks, into markets in the nation's capital or packaged and then shipped to be sold overseas, where demand for the whitefish is high.

Unclear origins

Are Canadian consumers unwittingly supporting child labour through seafood products they purchase in their local grocery store? People who’ve studied the issue say there’s no official tracking going on.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency inspects imported seafood to test for food safety risks and mislabelling, but its mandate doesn’t include investigating the supply lines to see if it includes child labour.

“The system is set up to protect us from injury and illness, because that’s what our regulations are focused on. But there’s a whole other side to a product that focuses on how it ends up on our table, and who might be exploited in that process,” said Cheryl Hotchkiss of World Vision Canada.

World Vision’s No Child for Sale campaign encourages Canadian companies to take more steps to ensure its supply chains support ethical labour practices. It's asking consumers to sign its petition to encourage Canadian governments and corporations to take more steps to ensure that global supply chains support good labour practices, and do more to address the root causes of child exploitation.

Hotchkiss said for the most part it’s up to individual companies to protect its workers, although many fish producers are still using child labour – and even slave labour – to get its product to international markets.

“The conversation we want to have with the Canadian government is that other side of the puzzle,” she said.

“We want to know who’s involved in the harvesting of those fish and seafood products because as consumers we want to know we’re not part of another kind of problem.”

World Day against Child Labour

Thursday marks the World Day against Child Labour and while it's hard to pinpoint the exact number of children working in the fishing industries in Uganda and elsewhere, the International Labour Organization says the global fishing industry is one of the biggest employers of child labour, along with mining, agriculture and manufacturing.

The number of children working is staggering: The ILO says 168 million children worldwide are engaged in child labour. Of those, 85 million are engaged in the most hazardous forms — nearly 15 times the population of children in Canada. It’s calling for affected countries to introduce social security systems to help fight the problem and more local protection programs that reach out specifically to groups of vulnerable children.

Children are most at risk when families lack basic resources like income and health care. Many kids start working in order to pay their school fees and then drop out because their families become dependent on the meagre income. So solving the problem of child labour isn't as easy as removing the child from the work. Local governments, organizations and NGOs need to help them and their families’ access basic needs, including getting the kids back to school, if they hope to end the cycle.

Some small positive changes are being made. The U.S. Department of Labour recently threatened sanctions against Ghana after learning that thousands of children — most under the age of 12 — are being forced to work in its tilapia industry. The government agency said tilapia farming specifically targeted young children, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Making the change

Greater transparency for companies and products appears to be a cause Canadians are rallying behind. An Ipsos Reid poll released after the 2013 Rana factory collapse in Bangladesh found that 87 per cent of Canadians want our government to ensure that Canadian companies don't directly or indirectly support poor labour practices, including child labour.

Canadians polled also expressed frustration about how hard it is to find out where their food and consumer products come from: 77 per cent said they felt frustrated about how difficult it is to determine where the products they buy are made, and who makes them.

World Vision says consumers can make a difference through the products they choose to buy, and the companies they support. By buying goods from companies that are working to address child labour it can actually spur other companies into taking action, said Hotchkiss. An overwhelming amount of consumers polled recently by Ipsos Reid for the NGO -- 87 per cent -- said they would pay more for products that were guaranteed to be free from child labour.

CTV Vancouver's Darcy Wintonyk travelled to East Africa to tour World Vision supported projects in May 2014.