A young swimmer whose entire left side was paralyzed as a result of the chicken pox says he can’t believe the rates of people choosing not to get some vaccines are on the rise.

Nathan Clement, 19, says he’s recovered some use in his arms and legs and is now training to swim for Canada in international swimming competitions. But he hopes his example could convince people who doubt vaccines are necessary to change their minds.

“Take the vaccine,” Clement told CTV News. “Personally I’m happy how I am now. I enjoy the opportunities I have in life. But it’s important not to take the risk.”

A measles outbreak in the Fraser Valley has reached some 200 cases. Measles is easily preventable through a vaccine.

While vaccination rates for measles are holding steady around 87 per cent provincially, other vaccine rates, such as the five-in-one vaccine that prevents polio and tetanus, have dropped 5 per cent in the past decade, to only 75 per cent provincially.

Clement had the chicken pox, also known as varicella, as an infant. In 1997, at the age of two, he had a stroke while riding in the back of his mom Janet Clement’s car.

“All of a sudden he wasn’t talking. I looked up at the rear view mirror and his eyeballs had rolled back in his head and the left side of his body had completely lost function,” Janet Clement said.

The family searched for a cause, and found themselves in Toronto talking to specialists. One of them told the family that it was extremely likely that the stroke was caused by chicken pox scars that had built up in the brain, broke off in the bloodstream, and blocked a crucial brain blood vessel.

It may be a surprise to hear that could happen from a disease that was thought of as a rite of passage of childhood, but doctors say chicken pox can have severe side effects and can even kill.

“Only a few per cent of kids get into trouble with chicken pox,” said Dr. David Scheifele, an infectious disease specialist and director of the Vaccine Evaluation Centre at the BC Children’s Hospital. “But things happen that put kids in hospital with severe secondary skin infections, flesh-eating disease, pneumonia, and brain inflammation.”

In 1997, the vaccine was available but it was not part of the B.C. vaccine schedule. In 2005, B.C. introduced a vaccine program for infants. By 2012, 89.3 per cent of kindergarten-age children in B.C. were vaccinated.

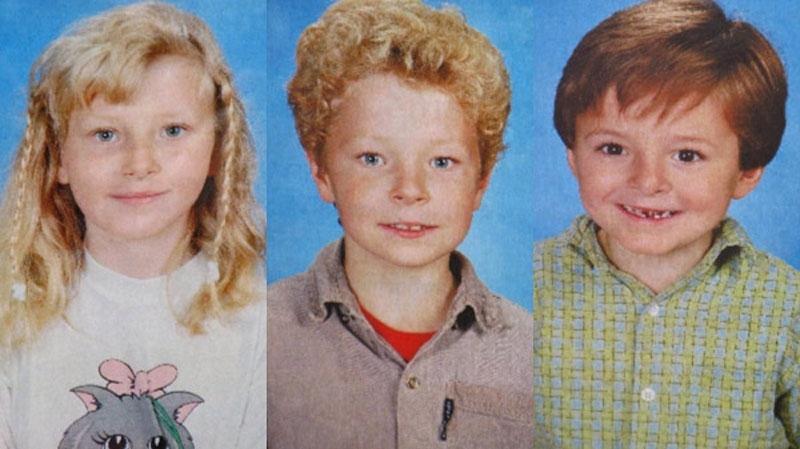

“My other two children, when I heard there was such a thing as the chicken pox vaccination, I had them vaccinated right away,” said Janet Clement.

Clement has a condition known as dystonia, which is a problem with nervous signals from the brain. It means that when he tries to use his left side to pick something up, for example, his body fights back and refuses the motion.

However, if he is distracted or doing a repetitive motion, such as swimming, he can use his limbs better. Clement is now competing in the butterfly, and hopes to represent Canada at the Paralympics one day.

Another virus – polio – paralyzed Jeanette Andersen, a Vancouver disability advocate, from the neck down.

Anderson contracted the disease in 1955, a few years after her brother died of the measles.

Polio was known as the “middle-class plague” or “the crippler” because it infected central nervous systems and destroyed patients’ ability to move muscles, including their ability to breathe.

Outbreaks in Canada in the first part of the 20th century were terrifying. Polio closed pools. Victims were treated in iron lungs to help them breathe, or in floating pools for lost muscle control. But even if patients survived the disease, they faced lifelong paralysis.

A vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk proved effective in the early 1950s. In 1954, the polio vaccine was in widespread field trials, with over 1.8-million American children participating.

The Canadian polio trials began on April 1 of that year using the Connaught vaccine, which had been developed in Toronto. It was shared for free to children in grades 1 to 3, who were considered most susceptible to polio.

Andersen said that she didn’t realize that the vaccine could have been given to teens and adults as well.

“They were doing vaccinations for kids one and two,” she said. “At 16, and very active, getting a vaccination was the last thing you’d think of.”

She said for the first five years after contracting the disease, she didn’t want to go out, and didn’t want people to see her.

“I don’t think I dwell on it because once something’s done, it’s done. You gradually move on to other things. You be involved. Keep the grey sails going,” she joked.

Andersen is now on the board of the B.C. Coalition for People With Disabilities, and also on the board of the Disabled Independent Gardeners Association.

And her message to the people who think vaccines are dangerous is: get educated.

“It’s simply a lack of education. You can’t really tell people what to do and what not to do. All of my (friends) do it. They don’t take the chance,” she said.