After decades of debate, a high-profile squat and years of construction, the renovated Woodwards development in the Downtown Eastside opened its doors Thursday to a handful of new homeowners - and more are soon to come.

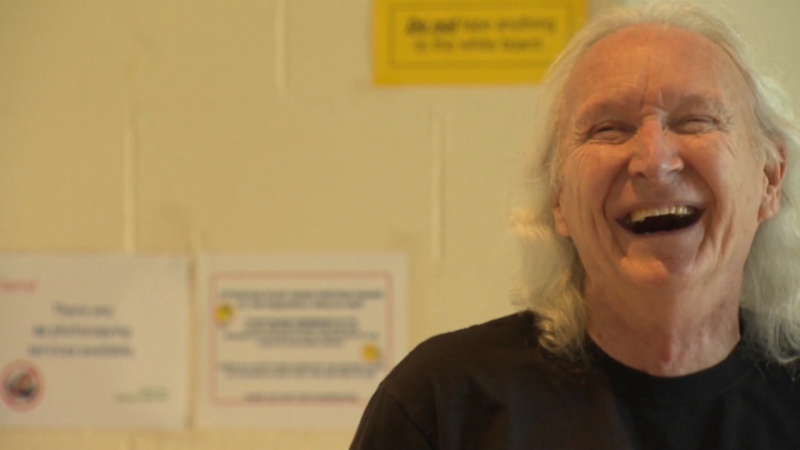

Former Vancouver city councillor Jim Green says he's looked forward to this day for decades.

"I've been here for every brick that's gone into it," he said. "It's the largest development ever on a single site in Vancouver."

In September 2002, the vacant Woodwards building was seized by housing activists and squatters, spurring a massive controversy in Vancouver. Seven years later, the renovated complex is opening to a variety of tenants - offering a unique mix of market and social housing.

And while some criticize the project for not giving priority to its social housing units, Green says organizers did what they could.

"People come and say. 'You should have had 600 units of social housing,'" Green said. "You have to do the best you can with you have, and I'm very proud of what we have here today."

The building's 500 market housing units will be turned over to residents over the next few weeks, and the 200 social housing units are expected to be ready in November.

Law student Danielle Glass bought a one bedroom unit at Woodwards. She works in Langley, but is willing to commute every day for the chance to live there.

"This building itself is a piece of Vancouver history," she said. "I feel like I'm part of a community now that I think is going to change and needs focus and attention."

But not everyone is so optimistic. Dave Cunningham of the Downtown Eastside Residents Association says projects like the Woodwards renovation are simply social cleansing.

"There's a lot of concern about how will the yuppies persevere amongst the poverty," he said. "And until that happened of course there wasn't any concern, it was just poor people dying."

People are being forced out of these re-developed areas, Cunningham says, and are just heading further east.

"They're ticked under the safe street act, they're harassed by police," he said. "Sooner than later they end up in the hospital or jail and then they're recycled back out into shelters and on to the streets."

With files from CTV British Columbia's Shannon Paterson and Norma Reid