VANCOUVER - British Columbia's pine-beetle devastated forest is belching out enough carbon to equal Canada's average annual forest fire emissions, says a new report from scientists at the Ministry of Natural Resources Canada.

Instead of manufacturing oxygen as it should, the damaged forest is becoming a source for global warming, putting more pressure on the need to reduce greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

The study, released Wednesday, calculates it will be much harder for Canada to meet global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions when a huge section of B.C. forests is putting out carbon dioxide.

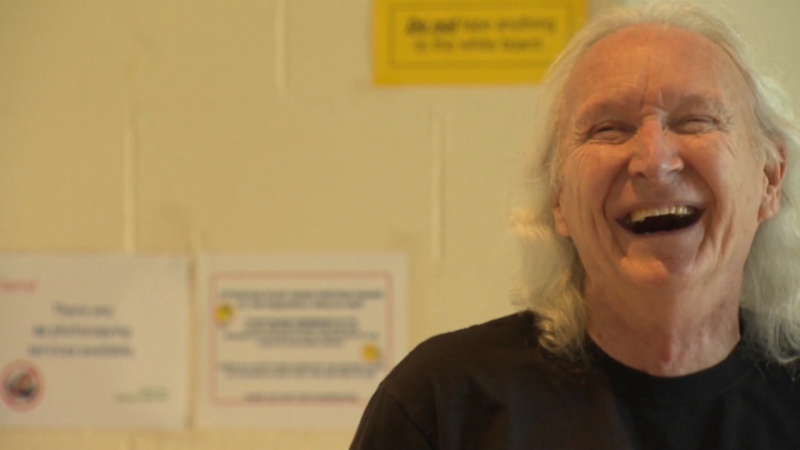

"What we're saying is what has historically helped us attain moderate growth rates of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere is, at least temporarily, in this region interrupted by the beetle,'' said Werner Kurz, the study's co-author.

Kurz, a senior research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service of Natural Resources Canada, has been working on the equation of carbon input and output of Canada's forests since 1989.

The model works so well he's training academics in Russia, Mexico and North America, on how to calculate the carbon balance of forests.

The study, which will be featured in the science journal Nature this week, adds a new dimension to the world-wide debate on global warming.

"For the first time we are able to isolate the impact of the beetle by creating the model infrastructure that allows us to represent the landscape with and without the beetle,'' Kurz said.

Last month, the B.C. government announced that the voracious pest has destroyed nearly half of British Columbia's marketable pine forest.

Approximately 13.5 million hectares of lodgepole pine in the province have been infested -- an area more than four times the size of Vancouver Island.

The beetle is now push east past the Rocky Mountains and into B.C.'s southern interior region.

Researchers estimated that from 2000 to 2020, a 374,000-square kilometre area of B.C. forest (an area larger than Labrador) would produce 270,000 megatonnes of carbon.

Kurz said that's about the same amount of carbon put out by Canada's entire transportation sector over a five-year period.

"So these are very large numbers in terms of impacts to the atmosphere,'' he said.

Scientists use the term carbon sink for a forest, ocean or other system that absorbs carbon dioxide. B.C.'s vast tracts of boreal forest have been considered a key carbon sink for the world.

Now Kurz said B.C.'s beetle-infested forest is a carbon source.

"Historically about 50 per cent of the carbon that is released from the burning of fossil fuels has been taken up by terrestrial systems and oceans, allowing only about half of what we burn for fossil fuel to accumulate in the atmosphere,'' he explained. "With these kinds of impacts on forests that sink in the forests is, temporarily at least, not going to be operating.''

The seed of the pine beetle devastation goes back to between 1880 and 1920 when wildfires swept through North America.

The lodgepole pines, which need fire to release their seeds, regenerated millions of trees. And 100-year-old pine trees are prime targets for the rice-sized mountain pine beetle.

Warmer winters in B.C.'s Interior region helped the pest spread faster and higher into the mountain passes, killing the trees and turning millions of hectares of prime pine forests a rusty red.

"If there were something that could have been done, it would have been tried at the beginning of the outbreak,'' Kurz said.

There are ways to mitigate the damage, including pulling the dead wood from the forests before the decaying timber pushes more carbon into the atmosphere.

Kurz suggests some of that wood could be used as a biofuel, that isn't in competition with human needs for cleaner fuel such as corn or sugar.

"We have a material that is bestowed upon us through the impacts of wildfires, insects, drought and other processes and we have a choice to make,'' Kurz said.

The other solution is silvaculture, planting millions of trees to compensate for the trees being lost.

The provincial government just recently announced that it had planted its sixth billionth tree since 1930.

But Kurz said those are all political decisions to make, and he's only doing the research that raises the alarm.

"You can see this forest is eventually going to recover and regrown trees will eventually take up more carbon dioxide than the dead trees are releasing.''